esp32 lcd display quotation

A few weeks ago, we examined the features of ESP32 module and built a simple hello world program to get ourselves familiar with the board. Today, we will continue our exploration of the ESP32 on a higher level as we will look at how to interface a 16×2 LCD with it.

Displays provide a fantastic way of providing feedback to users of any project and with the 16×2 LCD being one of the most popular displays among makers, and engineers, its probably the right way to start our exploration. For today’s tutorial, we will use an I2C based 16×2 LCD display because of the easy wiring it requires. It uses only four pins unlike the other versions of the display that requires at least 7 pins connected to the microcontroller board.

ESP32 comes in a module form, just like its predecessor, the ESP-12e, as a breakout board is usually needed to use the module. Thus when it’s going to be used in applications without a custom PCB, it is easier to use one of the development boards based on it. For today’s tutorial, we will use the DOIT ESP32 DevKit V1 which is one of the most popular ESP32 development boards.

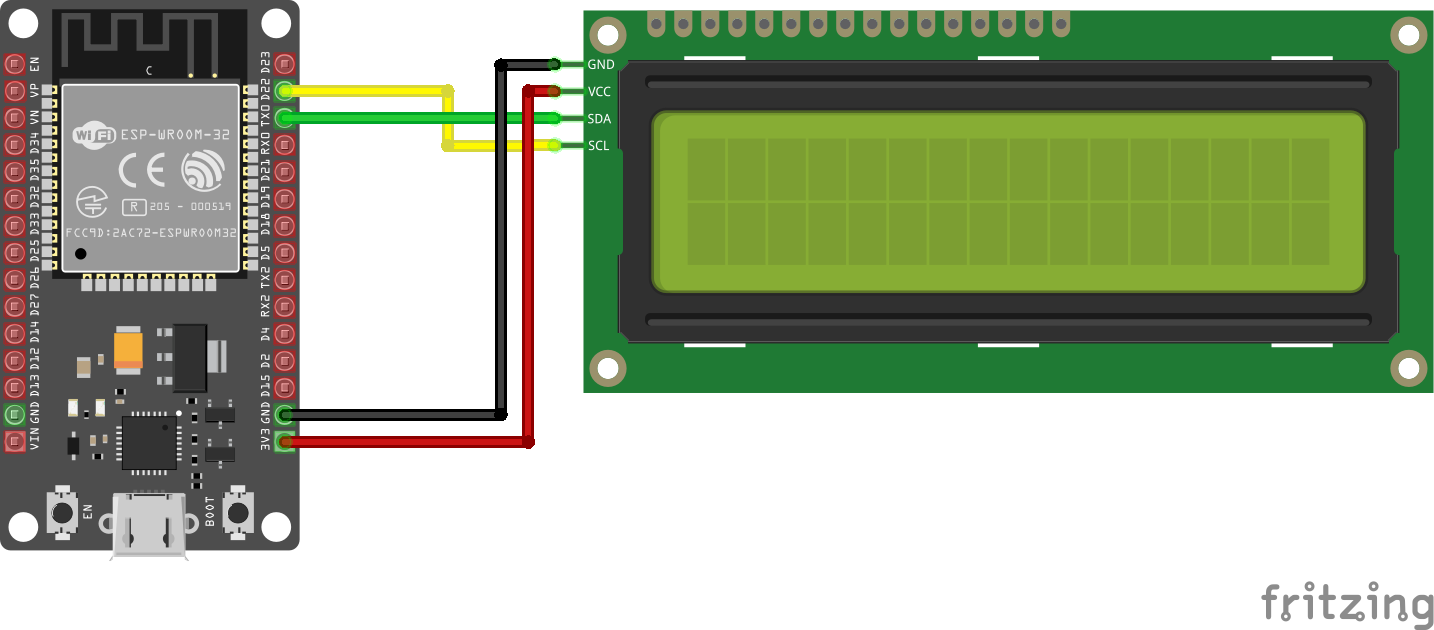

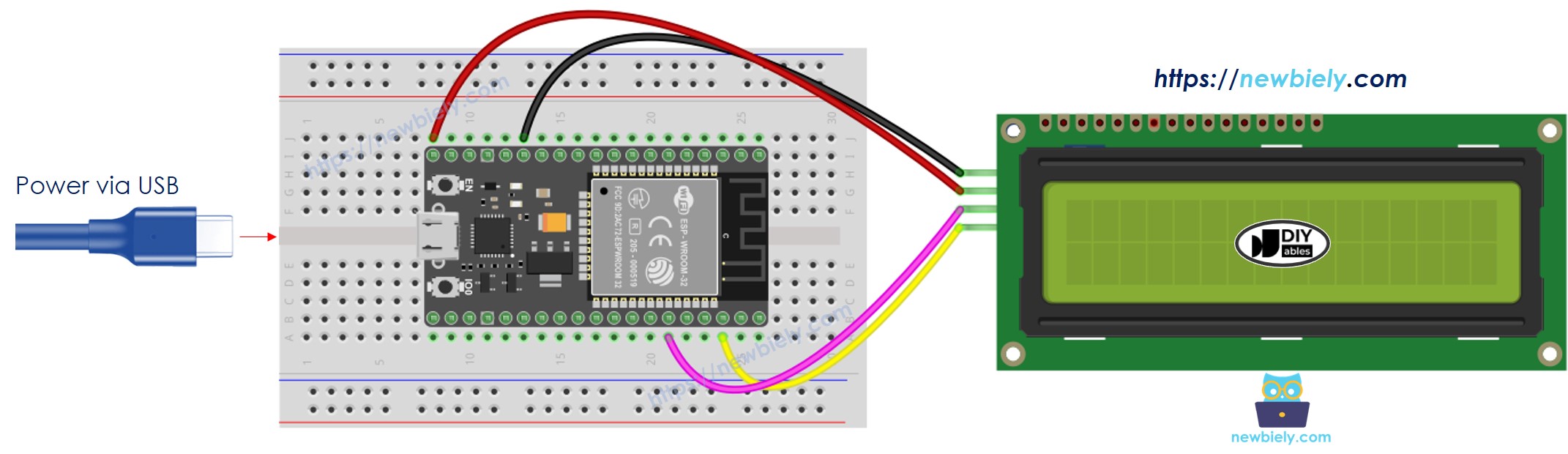

The schematics for this project is relatively simple since we are connecting just the LCD to the DOIT Devkit v1. Since we are using I2C for communication, we will connect the pins of the LCD to the I2C pins of the DevKit. Connect the components as shown below.

Due to the power requirements of the LCD, it may not be bright enough when connected to the 3.3v pin of the ESP32. If that is the case, connect the VCC pin of the LCD to the Vin Pin of the ESP32 so it can draw power directly from the connected power source.

At this point, it is important to note that a special setup is required to enable you to use the Arduino IDE to program ESP32 based boards. We covered this in the introduction to ESP32 tutorial published a few weeks go. So, be sure to check it out.

To be able to easily write the code to interact with the I2C LCD display, we will use the I2C LCD library. The Library possesses functions and commands that make addressing the LCD easy. Download the I2C LCD library from the link attached and install on the Arduino IDE by simply extracting it into the Arduino’s library folder.

Before writing the code for the project, it’s important for us to know the I2C address of the LCD as we will be unable to talk to the display without it.

While some of the LCDs come with the address indicated on it or provided by the seller, in cases where this is not available, you can determine the address by using a simple sketch that sniffs the I2C line to detect what devices are connected alongside their address. This sketch is also a good way to test the correctness of your wiring or to determine if the LCD is working properly.

If you keep getting “no devices found”, it might help to take a look at the connections to be sure you didn’t mix things up and you could also go ahead and try 0x27 as the I2C address. This is a common address for most I2C LCD modules from China.

Our task for today’s tutorial is to display both static and scrolling text on the LCD, and to achieve that, we will use the I2C LCD library to reduce the amount of code we need to write. We will write two separate sketches; one to displaystatic textsand the other to display both static and scrolling text.

To start with the sketch for static text display, we start the code by including the library to be used for it, which in this case, is the I2C LCD library.

Next, we create an instance of the I2C LCD library class with the address of the display, the number of columns the display has (16 in this case), and the number of rows (2 in this case) as arguments.

With that done, we proceed to the void setup() function. Here we initialize the display and issue the command to turn the backlight on as it might be off by default depending on the LCD.

Next is the void loop() function. The idea behind the code for the loop is simple, we start by setting the cursor to the column and row of the display where we want the text to start from, and we proceed to display the text using the lcd.print() function. To allow the text to stay on the screen for a while (so its visible) before the loop is reloaded, we delay the code execution for 1000ms.

For the scrolling text, we will use some code developed by Rui Santos of RandomNerdTutorials.com. This code allows the display of static text on the first row and scrolling text on the second row of the display at the same time.

Next, we create an instance of the I2C LCD library class with the address of the display, the number of columns the display has (16 in this case), and the number of rows (2 in this case) as arguments.

Next, we create the function to display scrolling text. The function accepts four arguments; the row on which to display the scrolling text, the text to be displayed, the delay time between the shifting of characters, and the number of columns of the LCD.

Next is the void setup() function. The function stays the same as the one for the static text display as we initialize the display and turn on the backlight.

With that done, we move to the void loop() function. We start by setting the cursor, then we use the print function to display the static text and the scrollText() function is called to display the scrolling text.

Ensure your connections are properly done, connect the DOIT Devkit to your PC and upload either of the two sketches. You should see this display come up with the text as shown in the image below.

That’s it for today’s tutorial guys. Thanks for following this tutorial. This cheap LCD display provides a nice way of providing visual feedback for your project and even though the size of the screen and the quality of the display is limited, with the scrolling function you can increase the amount of text/characters that can be displayed.

Than displays are the way to go. There are different kinds of displays like 7 Segment LED display, 4 Digit 7 Segment display, 8×8 Dot Matrix display, OLED display or the easiest and cheapest version the liquid crystal display (LCD).

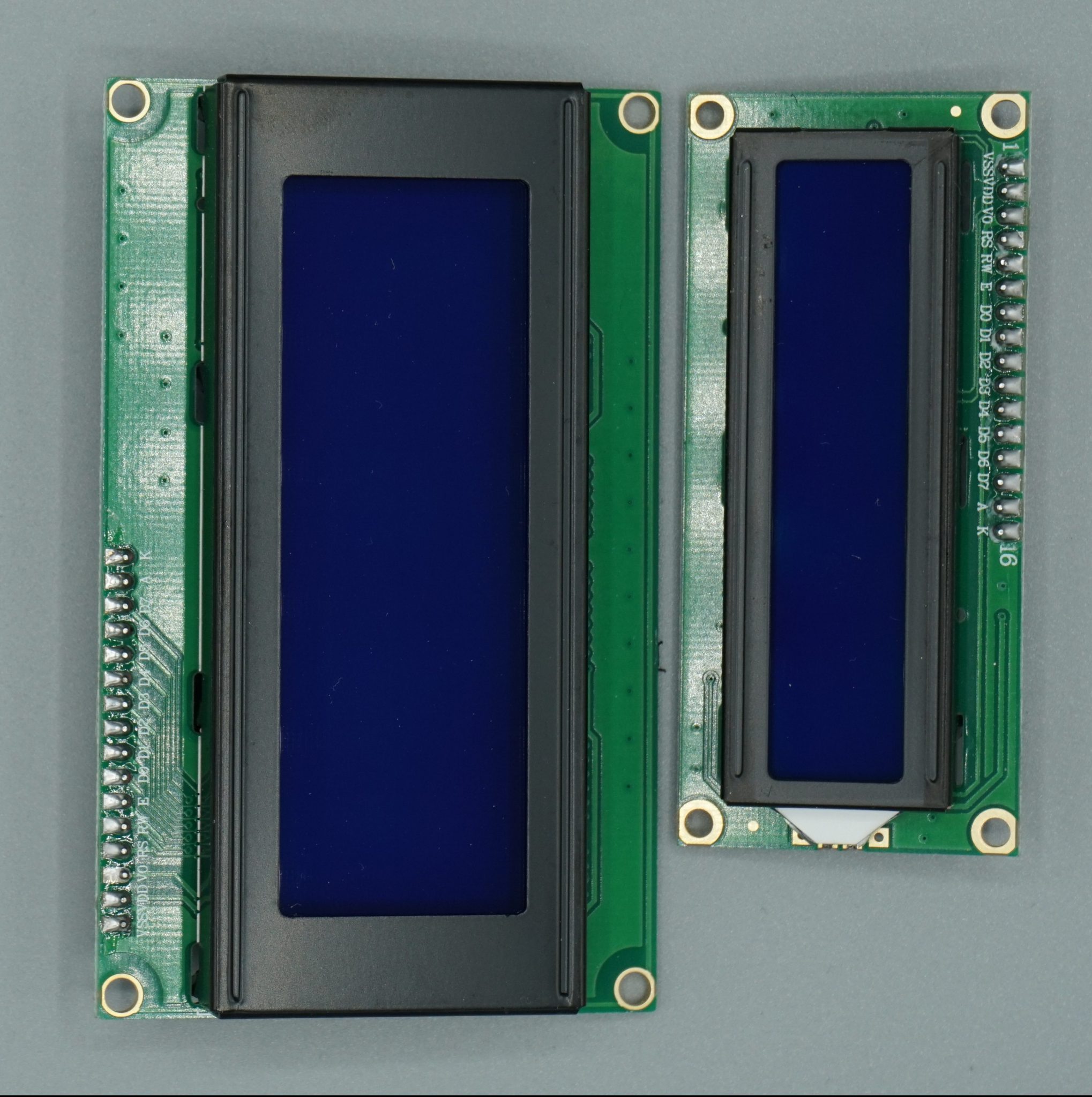

Most LCD displays have either 2 rows with 16 characters per row or 4 rows with 20 characters per row. There are LCD screen with and without I2C module. I highly suggest the modules with I2C because the connection to the board is very easy and there are only 2 instead of 6 pins used. But we will cover the LCD screen with and without I2C module in this article.

The LCD display has an operating voltage between 4.7V and 5.3V with a current consumption of 1mA without backlight and 120mA with full backlight. There are version with a green and also with a blue backlight color. Each character of the display is build by a 5×8 pixel box and is therefore able to display custom generated characters. Because each character is build by (5×8=40) 40 pixels a 16×2 LCD display will have 16x2x40= 1280 pixels in total. The LCD module is able to operate in 8-bit and 4-bit mode. The difference between the 4-bit and 8-bit mode are the following:

If we use the LCD display version without I2C connection we have to add the potentiometer manually to control the contrast of the screen. The following picture shows the pinout of the LCD screen.

Also I added a table how to connect the LCD display with the Arduino Uno and the NodeMCU with a description of the LCD pin. To make it as easy as possible for you to connect your microcontroller to the display, you find the corresponding fritzing connection picture for the Arduino Uno and the NodeMCU in this chapter.

3VEEPotentiometerPotentiometerAdjusts the contrast of the display If this pin is grounded, you get the maximum contrast. We will connect the VEE pin to the potentiometer output to adjust the contrast by changing the resistance of the potentiometer.

4RSD12D2Select command register to low when we are sending commands to the LCD like set the cursor to a specific location, clear the display or turn off the display.

8Data Pin 1 (d1)Data pins 0 to 7 forms an 8-bit data line. The Data Pins are connection to the Digital I/O pins of the microcontroller to send 8-bit data. These LCD’s can also operate on 4-bit mode in such case Data pin 4,5,6 and 7 will be left free.

Of cause we want to try the connection between the microcontroller and the LCD display. Therefore you find an example sketch in the Arduino IDE. The following section shows the code for the sketch and a picture of the running example, more or less because it is hard to make a picture of the screen ;-). The example prints “hello, world!” in the first line of the display and counts every second in the second row. We use the connection we described before for this example.

Looks very complicated to print data onto the LCD screen. But don’t worry like in most cases if it starts to get complicated, there is a library to make the word for us. This is also the case for the LCD display without I2C connection.

Like I told you, I would suggest the LCD modules with I2C because you only need 2 instead of 6 pins for the connection between display and microcontroller board. In the case you use the I2C communication between LCD and microcontroller, you need to know the I2C HEX address of the LCD. In this article I give you a step by step instruction how to find out the I2C HEX address of a device. There is also an article about the I2C communication protocol in detail.

The following picture shows how to connect an I2C LCD display with an Arduino Uno. We will use exact this connection for all of the examples in this article.

To use the I2C LCD display we have to install the required library “LiquidCrystal_I2C” by Frank de Brabander. You find here an article how to install an external library via the Arduino IDE. After you installed the library successful you can include the library via: #include < LiquidCrystal_I2C.h>.

The LiquidCrystal library has 20 build in functions which are very handy when you want to work with the LCD display. In the following part of this article we go over all functions with a description as well as an example sketch and a short video that you can see what the function is doing.

LiquidCrystal_I2C()This function creates a variable of the type LiquidCrystal. The parameters of the function define the connection between the LCD display and the Arduino. You can use any of the Arduino digital pins to control the display. The order of the parameters is the following: LiquidCrystal(RS, R/W, Enable, d0, d1, d2, d3, d4, d5, d6, d7)

If you are using an LCD display with the I2C connection you do not define the connected pins because you do not connected to single pins but you define the HEX address and the display size: LiquidCrystal_I2C lcd(0x27, 20, 4);

xlcd.begin()The lcd.begin(cols, rows) function has to be called to define the kind of LCD display with the number of columns and rows. The function has to be called in the void setup() part of your sketch. For the 16x2 display you write lcd.begin(16,2) and for the 20x4 lcd.begin(20,4).

xxlcd.clear()The clear function clears any data on the LCD screen and positions the cursor in the upper-left corner. You can place this function in the setup function of your sketch to make sure that nothing is displayed on the display when you start your program.

xxlcd.setCursor()If you want to write text to your LCD display, you have to define the starting position of the character you want to print onto the LCD with function lcd.setCursor(col, row). Although you have to define the row the character should be displayed.

xxlcd.print()This function displays different data types: char, byte, int, long, or string. A string has to be in between quotation marks („“). Numbers can be printed without the quotation marks. Numbers can also be printed in different number systems lcd.print(data, BASE) with BIN for binary (base 2), DEC for decimal (base 10), OCT for octal (base 8), HEX for hexadecimal (base 16).

xlcd.println()This function displays also different data types: char, byte, int, long, or string like the function lcd.print() but lcd.println() prints always a newline to output stream.

xxlcd.display() / lcd.noDisplay()This function turn on and off any text or cursor on the display but does not delete the information from the memory. Therefore it is possible to turn the display on and off with this function.

xxlcd.scrollDisplayLeft() / lcd.scrollDisplayRight()This function scrolls the contents of the display (text and cursor) a one position to the left or to the right. After 40 spaces the function will loops back to the first character. With this function in the loop part of your sketch you can build a scrolling text function.

Scrolling text if you want to print more than 16 or 20 characters in one line, than the scrolling text function is very handy. First the substring with the maximum of characters per line is printed, moving the start column from the right to the left on the LCD screen. Than the first character is dropped and the next character is printed to the substring. This process repeats until the full string is displayed onto the screen.

xxlcd.autoscroll() / lcd.noAutoscroll()The autoscroll function turn on or off the functionality that each character is shifted by one position. The function can be used like the scrollDisplayLeft / scrollDisplayRight function.

xxlcd. leftToRight() / lcd.rightToLeft()The leftToRight and rightToLeft functions changes the direction for text written to the LCD. The default mode is from left to right which you do not have to define at the start of the sketch.

xxlcd.createChar()There is the possibility to create custom characters with the createChar function. How to create the custom characters is described in the following chapter of this article as well as an example.

xlcd.backlight()The backlight function is useful if you do not want to turn off the whole display (see lcd.display()) and therefore only switch on and off the backlight. But before you can use this function you have to define the backlight pin with the function setBacklightPin(pin, polarity).

xlcd.moveCursorLeft() / lcd.moveCursorRight()This function let you move the curser to the left and to the right. To use this function useful you have to combine it with lcd.setCursor() because otherwise there is not cursor to move left or right. For our example we also use the function lcd.cursor() to make the cursor visible.

xlcd.on() / lcd.off()This function switches the LCD display on and off. It will switch on/off the LCD controller and the backlight. This method has the same effect of calling display/noDisplay and backlight/noBacklight.

Show or hide a cursor (“_”) that is useful when you create a menu as navigation bar from the left to the right or from the top to the bottom, depending on a horizontal of vertical menu bar. If you are interested how to create a basic menu with the ESP or Arduino microcontroller in combination with the display, you find here a tutorial.

The following code shows you the Arduino program to use all three LCD display functions of the library divided into three separate functions. Also the video after the program shows the functions in action.

The creation of custom characters is very easy if you use the previous mentioned libraries. The LiquidCrystal and also the LiquidCrystal_I2C library have the function “lcd.createChar()” to create a custom character out of the 5×8 pixels of one character. To design your own characters, you need to make a binary matrix of your custom character from an LCD character generator or map it yourself. This code creates a wiggling man.

In the section of the LCD display pinout without I2C we saw that if we set the RS pin to how, that we are able to send commands to the LCD. These commands are send by the data pins and represented by the following table as HEX code.

were missing for my display (hailege, 2,8 tft, spi, il9431, https://www.amazon.de/-/en/gp/product/B07YTWRZGR/ref=ppx_yo_dt_b_asin_title_o04_s00?ie=UTF8&psc=1). so it might just be that the led backlight isnt being turned on. but of course the tip might not help with the st7796s.

The 320*240 TFT LCD provides enough screen space to show the stock’s ticker symbol, company name, current price, price change, 52 week high/low visual, price change percent, P/E, open price, quote time, and other system related status indicators. The color of the price is either red, green, or magenta which indicates price down days, price up days, or weekends/holidays.

A possible future version would decrease the bezel around the display by creating a custom PCB to provide a TFT mount without the extra space for headers. The ESP32 and logic level converter would attach to the PCB to eliminate all but the power wires. The PCB will also allow reducing the amount the SD card protrudes from the display housing.

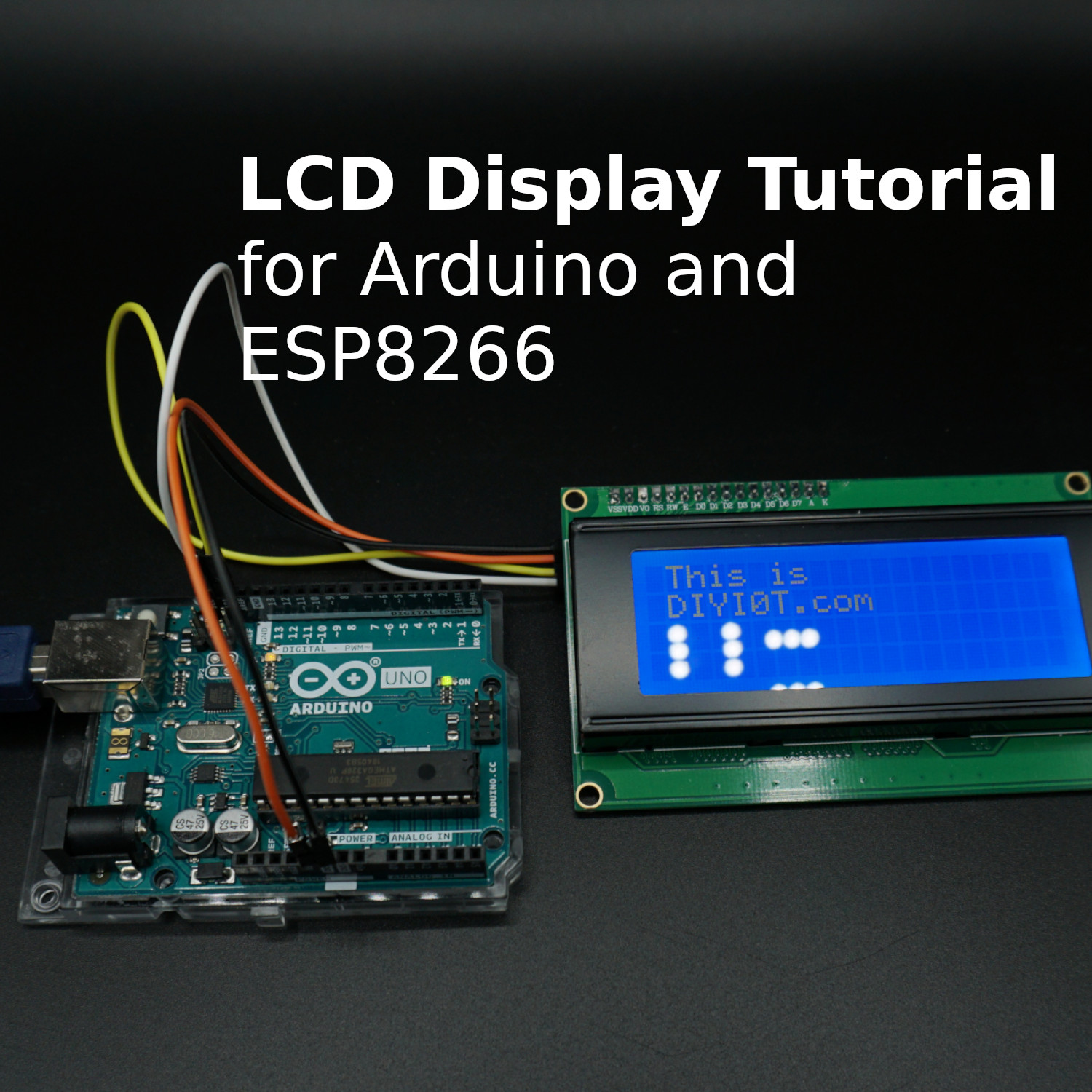

This tutorial shows how to use the I2C LCD (Liquid Crystal Display) with the ESP32 using Arduino IDE. We’ll show you how to wire the display, install the library and try sample code to write text on the LCD: static text, and scroll long messages. You can also use this guide with the ESP8266.

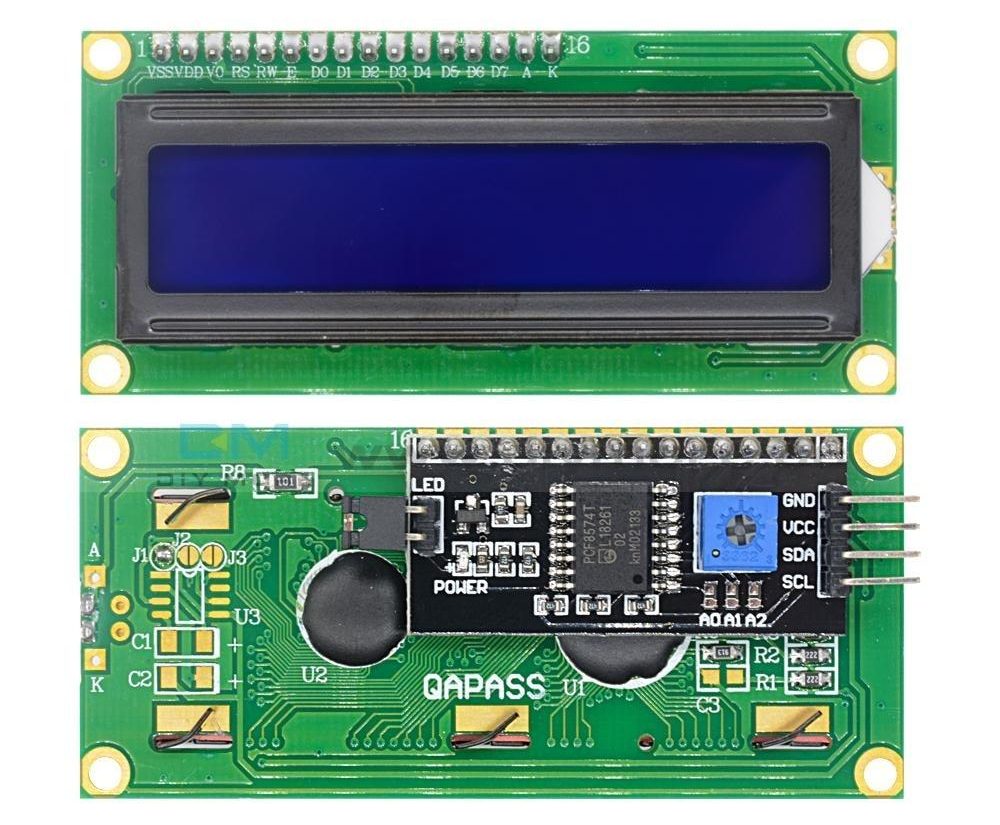

Additionally, it comes with a built-in potentiometer you can use to adjust the contrast between the background and the characters on the LCD. On a “regular” LCD you need to add a potentiometer to the circuit to adjust the contrast.

Before displaying text on the LCD, you need to find the LCD I2C address. With the LCD properly wired to the ESP32, upload the following I2C Scanner sketch.

After uploading the code, open the Serial Monitor at a baud rate of 115200. Press the ESP32 EN button. The I2C address should be displayed in the Serial Monitor.

Displaying static text on the LCD is very simple. All you have to do is select where you want the characters to be displayed on the screen, and then send the message to the display.

The next two lines set the number of columns and rows of your LCD display. If you’re using a display with another size, you should modify those variables.

Then, you need to set the display address, the number of columns and number of rows. You should use the display address you’ve found in the previous step.

To display a message on the screen, first you need to set the cursor to where you want your message to be written. The following line sets the cursor to the first column, first row.

Scrolling text on the LCD is specially useful when you want to display messages longer than 16 characters. The library comes with built-in functions that allows you to scroll text. However, many people experience problems with those functions because:

The messageToScroll variable is displayed in the second row (1 corresponds to the second row), with a delay time of 250 ms (the GIF image is speed up 1.5x).

In a 16×2 LCD there are 32 blocks where you can display characters. Each block is made out of 5×8 tiny pixels. You can display custom characters by defining the state of each tiny pixel. For that, you can create a byte variable to hold the state of each pixel.

In summary, in this tutorial we’ve shown you how to use an I2C LCD display with the ESP32/ESP8266 with Arduino IDE: how to display static text, scrolling text and custom characters. This tutorial also works with the Arduino board, you just need to change the pin assignment to use the Arduino I2C pins.

We hope you’ve found this tutorial useful. If you like ESP32 and you want to learn more, we recommend enrolling in Learn ESP32 with Arduino IDE course.

Note: ESP32-S2 is a relatively new product, the ecosystem and support are still fresh. We do not recommend it for beginners. Do consider NodeMCU-ESP32 or T-Display.

This is LILYGO® TTGO T8 ESP32-S2 V1.1 ST77789 1.14 Inch LCD Display WIFI Wireless Module. It operates with an ESPRESSIF-ESP32-S2chipset. ESP32-S2 is a truly secure, highly integrated, low-power, 2.4 GHz Wi-Fi Microcontroller SoC supporting Wi-Fi HT40 and having 43 GPIOs.

This project uses the SPIFFS (ESP32 flash memory) to store images used as background. You"ll need to upload these to the ESP32 before you upload the sketch to the ESP32. For this you"ll need the ESP32 Sketch Data Upload tool.

You can download this from Github: "https://github.com/me-no-dev/arduino-esp32fs-plugin". Follow the instructions on the Github to install the tool:Download the tool archive from releases page.

Before you upload the data folder to the ESP32, you"ll first have to select the right partitioning scheme.Go to Tools -> Board and select ESP32 Dev Module.

Firstly, depending on the board you are using (with resistive touch, capacitive touch, or no touch) you will have to uncomment the correct one. For example, if you are using the ESP32 TouchDown uncomment: "#define ENABLE_CAP_TOUCH". If you are using a DevKitC with separate TFT, uncomment "#define ENABLE_RES_TOUCH".

You can also set the scale of the y-axis of the graphs. This is done under "// The scale of the Y-axis per graph". If these are to big or to small, the data will not be displayed correctly on the graph. You might have to experiment with these.

Go ahead and upload the Bluetooth-System-Monitor.ino sketch to the ESP32. The settings under tools besides the Partition Scheme can be left to the default (see image). Go to "Sketch" and select "Upload". This may take a while because it is a large sketch.

Want to display sensor readings in your ESP32 projects without resorting to serial output? Then an I2C LCD display might be a better choice for you! It consumes only two GPIO pins which can also be shared with other I2C devices.

True to their name, these LCDs are ideal for displaying only text/characters. A 16×2 character LCD, for example, has an LED backlight and can display 32 ASCII characters in two rows of 16 characters each.

If you look closely you can see tiny rectangles for each character on the display and the pixels that make up a character. Each of these rectangles is a grid of 5×8 pixels.

At the heart of the adapter is an 8-bit I/O expander chip – PCF8574. This chip converts the I2C data from an ESP32 into the parallel data required for an LCD display.

If you are using multiple devices on the same I2C bus, you may need to set a different I2C address for the LCD adapter so that it does not conflict with another I2C device.

An important point here is that several companies manufacture the same PCF8574 chip, Texas Instruments and NXP Semiconductors, to name a few. And the I2C address of your LCD depends on the chip manufacturer.

So your LCD probably has a default I2C address 0x27Hex or 0x3FHex. However it is recommended that you find out the actual I2C address of the LCD before using it.

Connecting I2C LCD to ESP32 is very easy as you only need to connect 4 pins. Start by connecting the VCC pin to the VIN on the ESP32 and GND to ground.

Now we are left with the pins which are used for I2C communication. We are going to use the default I2C pins (GPIO#21 and GPIO#22) of the ESP32. Connect the SDA pin to the ESP32’s GPIO#21 and the SCL pin to the ESP32’s GPIO#22.

After wiring up the LCD you’ll need to adjust the contrast of the display. On the I2C module you will find a potentiometer that you can rotate with a small screwdriver.

Plug in the ESP32’s USB connector to power the LCD. You will see the backlight lit up. Now as you turn the knob on the potentiometer, you will start to see the first row of rectangles. If that happens, Congratulations! Your LCD is working fine.

The I2C address of your LCD depends on the manufacturer, as mentioned earlier. If your LCD has a Texas Instruments’ PCF8574 chip, its default I2C address is 0x27Hex. If your LCD has NXP Semiconductors’ PCF8574 chip, its default I2C address is 0x3FHex.

So your LCD probably has I2C address 0x27Hex or 0x3FHex. However it is recommended that you find out the actual I2C address of the LCD before using it. Luckily there’s an easy way to do this. Below is a simple I2C scanner sketch that scans your I2C bus and returns the address of each I2C device it finds.

After uploading the code, open the serial monitor at a baud rate of 115200 and press the EN button on the ESP32. You will see the I2C address of your I2C LCD display.

But, before you proceed to upload the sketch, you need to make a small change to make it work for you. You must pass the I2C address of your LCD and the dimensions of the display to the constructor of the LiquidCrystal_I2C class. If you are using a 16×2 character LCD, pass the 16 and 2; If you’re using a 20×4 LCD, pass 20 and 4. You got the point!

First of all an object of LiquidCrystal_I2C class is created. This object takes three parameters LiquidCrystal_I2C(address, columns, rows). This is where you need to enter the address you found earlier, and the dimensions of the display.

In ‘setup’ we call three functions. The first function is init(). It initializes the LCD object. The second function is clear(). This clears the LCD screen and moves the cursor to the top left corner. And third, the backlight() function turns on the LCD backlight.

After that we set the cursor position to the third column of the first row by calling the function lcd.setCursor(2, 0). The cursor position specifies the location where you want the new text to be displayed on the LCD. The upper left corner is assumed to be col=0, row=0.

lcd.scrollDisplayRight() function scrolls the contents of the display one space to the right. If you want the text to scroll continuously, you have to use this function inside a for loop.

lcd.scrollDisplayLeft() function scrolls the contents of the display one space to the left. Similar to above function, use this inside a for loop for continuous scrolling.

If you find the characters on the display dull and boring, you can create your own custom characters (glyphs) and symbols for your LCD. They are extremely useful when you want to display a character that is not part of the standard ASCII character set.

CGROM is used to store all permanent fonts that are displayed using their ASCII codes. For example, if we send 0x41 to the LCD, the letter ‘A’ will be printed on the display.

CGRAM is another memory used to store user defined characters. This RAM is limited to 64 bytes. For a 5×8 pixel based LCD, only 8 user-defined characters can be stored in CGRAM. And for 5×10 pixel based LCD only 4 user-defined characters can be stored.

Creating custom characters has never been easier! We have created a small application called Custom Character Generator. Can you see the blue grid below? You can click on any 5×8 pixel to set/clear that particular pixel. And as you click, the code for the character is generated next to the grid. This code can be used directly in your ESP32 sketch.

After the library is included and the LCD object is created, custom character arrays are defined. The array consists of 8 bytes, each byte representing a row of a 5×8 LED matrix. In this sketch, eight custom characters have been created.

LILYGO® T-Display-S3 ESP32-S3 1.9 inch ST7789 LCD Display Development Board WIFI Bluetooth5.0 Wireless Module 170*320 Resolution T-Display-S3 is a development board whose main control chip is...

After creating an Internet connected digital clock using the Adafruit RA8875 driving an Adafruit seven inch LCD display (Figure 1), my thoughts turned to making a different model that didn’t use a slave Arduino Nano to drive the LCD display. (Refer to my previous article

My desire was to include several additional features as well, which would require more program space in the microcontroller that drives the LCD display. This new program would also make use of the LCD touch screen to allow a user to select different features of the device.

I selected the Arduino MKR Wi-Fi 1010 for replacing the ESP32 and Arduino Nano. It was tested with the RA8875 and LCD connected, and it worked fine. The MKR Wi-Fi 1010 has 256k program space — a vast improvement over the Nano. Plus, it has Internet connectivity. The WiFiNINA library the Wi-Fi 1010 uses for Internet connectivity includes an SSL client which allows access to secure websites.

Using this design, I wrote a lengthy program that included several additional features besides a digital clock: the ability to set an alarm; a countdown timer for uses like monitoring an exercise program; a weather display to provide brief conditions at 10 different cities; a real time stock market report that gives the changing prices for a selection of stocks; and lastly (just for fun), a Mandelbrot fractal generator to produce those wonderful images.

After having built this project with the single Arduino MKR Wi-Fi 1010, I was unhappy with it. Yes, that’s correct, I didn’t like it. The goal of having only one microcontroller in the project was achieved but, in my opinion, it was a mistake. There is something to be said for using a separate microcontroller for Internet connectivity and another one to drive the RA8875 and LCD display.

The microcontroller driving the LCD display doesn’t have to deal with the relatively slow Internet retrieval. Receiving data from the Internet takes some time; at least a fraction of a second and sometimes longer than a second or two. With the digital clock needing to be updated once a second, this can be a problem.

There was also another option I wanted to add: an SD card interface to allow me to store and display images on the LCD similar to a photo frame. An SD card interface utilizes the SPI library which is also used to drive the Adafruit RA8875. With Adafruit’s warning about needing to tri-state at least one SPI pin when sharing the SPI interface, a better solution would be a microcontroller with at least two SPI interfaces.

The Teensy 3.5 microcontroller looked like a good choice since it has three SPI interfaces, with one used by the built-in microSD card socket. It also has 512k Flash memory, 120 MHz clock speed, and is compatible with the RA8875 driving the LCD. The Arduino MKR Wi-Fi 1010 could still be used for the Internet connectivity, but an ESP32 has a faster clock speed and is one third the cost.

A last-minute addition to this project was to add Internet radio. With the ESP32 being able to stream radio stations off the Internet, all that was needed was a hardware MP3 decoder and an audio amplifier.

Instead of having the ESP32 sending updated information to the Teensy 3.5 on a regular schedule, the Teensy 3.5 sends requests for specific data to the ESP32. The ESP32 waits for these requests and when one arrives, it fetches the information from the Internet and returns it to the Teensy in a concise data string.

It’s similar to a simple client-server architecture except the two microcontrollers are connected by their serial ports running at 38,400 baud. Serial3 on the Teensy 3.5 is connected to Serial2 on the ESP32 (Figure 4).

When one of these request strings is received, the ESP32 sends its request through the Internet for the appropriate data. When the data is received, it’s parsed and then sent to the Teensy 3.5 as a concise string, which is then parsed by the Teensy to retrieve the data it requested.

While this might seem a little convoluted, it leaves the ESP32 waiting for the response from the Internet while the Teensy program can continue and update the clock display every second with time to spare. The ESP32 also continuously checks that it has Internet connectivity from the wireless router it’s using. If it loses its connection, it goes into a loop to reconnect.

When the Teensy 3.5 sends a radio string, the ESP32 connects to the current radio station and then enters an endless loop to read the continuous stream of the digitized radio signal sent from the Internet.

At this point, the ESP32 can’t read any requests sent from the Teensy 3.5 since it’s locked in the tight loop to read the radio stream. The only way to break out of the loop is through an external interrupt request.

The Teensy pin 14 is tied to the ESP32 pin 13, and pin 17 is tied to 14. You only need to go from a HIGH to a LOW state on pin 14 or 17 of the Teensy 3.5 for a few milliseconds to initiate an interrupt on the ESP32:

Interrupts are attached to pins 13 and 14 on the ESP32 for breaking out of the radio stream loop and changing a station, respectively. Note that you can’t use pin 12 on the ESP32 for an interrupt on this project.

When you try to download a program into the ESP32, pin 12 will be held HIGH by the Teensy 3.5 in its default state unless you remove it from its socket on the PCB. With pin 12 held HIGH, the ESP32 will not be able to receive a download.

The weather mode and stock market mode will also not work, as the full time of the ESP32 is occupied with reading the radio stream. These functions will be available again once the radio is turned off.

A flowchart for the ESP32 program is shown in Figure 5 and the Teensy 3.5 program in Figure 6. The bulk of the software resides in the Teensy 3.5 — about 2,000 total lines, including blanks and comments. However, that only uses 14% of the program space available.

The vast majority of the Teensy program code deals with writing to the LCD screen and reacting to the touch screen. Moving from graphic to text mode has a lot of overhead. After declaring text mode, you must set the size, set the color, place the cursor where you want to write the text, and then finally write the text from a character array.

The library for the RA8875 LCD driver also requires a character array when writing text on the screen which can be awkward. A string would have been preferred.

The software for both the Teensy 3.5 and ESP32 can be found in the download section for this article. Both programs contain several comments and Serial.print statements to help with understanding and debugging.

The Teensy 3.5 program operates in eight different modes. For example, Mode 0 displays the default time, temperature, humidity, and weather screen, while Mode 1 allows you to set and display a timer. A description of what each mode does follows.

Mode 0 is the default mode and does a lot of additional things besides displaying the time in large numbers at the top of the LCD display. One of the little tricks in this program is to only draw one of the large numbers if it changes. If we re-draw every number, it takes too long, and the result is a noticeable flicker in the time display. During seconds 0 through 3, we do specific things. Otherwise, we just wait for the next second to occur and then redraw the time:

Lastly, we check to see if our Home or Time request has been answered. If it has, then the data from the ESP32 is parsed and stored in the case of a Home request, or the time is reset if there’s a Time request.

If the LCD screen is touched while in Mode 0, it will display a simple menu screen allowing the mode to be changed. Touching the LCD screen or an Exit button when in one of the other modes will return you to Mode 0.

Mode 1 allows you to set a timer and then display it. This can be used to time an activity like an exercise program, for example. The set time counts down using the same style large numbers for the normal time display in Mode 0. At the end of the countdown, the alarm line is toggled and the radio turned on. A keyboard is displayed for entry, along with buttons to start the timer or exit.

The weather at 10 different chosen locations is displayed. The format is the same as the local weather display in Mode 0. The screen fills with the first five locations and then clears and displays the second five. The display hesitates between drawing each brief weather condition as a request is made to the ESP32 for each location, and then waits until the ESP32 returns the weather data.

Setting this mode displays a series of bitmap images that are stored on a microSD card. The Teensy 3.5 has a slot for the microSD card on the end opposite of the USB connector. These bitmap images can be any size that doesn’t exceed the LCD screen size. I purposefully made mine exactly 800x480 pixels. File names need to be restricted to eight characters and adhere to the 8.3 file naming system.

This mode does something similar to Mode 2, except it displays 10 different stock quotes in real time. The stocks were selected and their symbols added to the ESP32 program.

The number of options this site has for requesting data is almost overwhelming. I chose something simple, and although it sends a compact format, there is still a lot of information returned. I only extract the current price, but there is a lot more potential here. The program loops through the 10 chosen stocks and displays the current price. It then clears the LCD and repeats the display.

For my own amusement, I also included a function that draws 10 different Mandelbrot fractal images on the screen at a size of 480x480. I’ve been writing software to compute Mandelbrot images since the August 1985 issue of the Scientific American revealed them to the public. These have been my “Hello World” programs whenever I learned a new programming language. My millennial son says these images on the LCD make the best night light he’s ever had!

This PCB mounts the Teensy 3.5 and ESP32 along with a few other parts. In addition, it also has connectors to five other small breakout boards. These are the: RA8875 LCD driver; BME280 temperature and humidity sensor; DS3231 real time clock (RTC); VS1053 MP3 decoder; and the PAM8403 audio amplifier. The PCB pads for the ESP32 have been doubled up on one side allowing the use of an ESP32 with pin spacing across the board of either 0.9 or 1.0 inches wide.

Be sure to check that the ESP32 you have is pin compatible with this design which has 38 pins. Consider also the board size of the ESP32 and make sure it will not interfere with the nearby header pins that go to the MP3 decoder board. I used the HiLetgo ESP-WROOM-32 ESP32 ESP-32S development board.

There are places to mount three LEDs: one from the Teensy connected to pin 33; and two from the ESP32 connected to pins 2 and 4. These can be used to denote a good Internet connect or other testing or debugging functions.

The RA8875 LCD driver board is also a tight fit. There is a hole for a 4-40 machine screw on the PCB near pin 1 of the Teensy 3.5; a single stand-off was used here to mount the RA8875 driver board under the main PCB. Unfortunately, the Adafruit RA8875 board uses 2-56 size mounting holes, so a small printed tab with 2-56 and 4-40 holes was 3D printed to connect the RA8875 board to the 4-40 stand-off beneath the main PCB. This is illustrated in Figure 18.

For the project box itself, I designed and used my 3D printer to produce the custom design. Sketchup files along with object files are included in the download material. Also included are a back cover, the tabs for mounting the LCD display, the knob for the audio amplifier, and the tab to connect the RA8875 to the stand-off.

The object files can be used with the Cura slicer to produce gcode for many different 3D printers. I recommend this custom project box — especially because of the difficulty in mounting the Adafruit LCD which has no mounting holes or tabs whatsoever, making mounting a real challenge.

The project box mounts the LCD by placing it between three 1/4 inch stand-offs which then have small 3D printed tabs screwed down on the top of the stand-offs to press the LCD against the box wall.

Care needs to be taken to not press down on the LCD display too hard as the touch panel may register a continual touch, making reading it impossible. In retrospect, this box should have been made larger, allowing for an easier fit of the components. The two inch speakers just fit; anything larger will require a larger project box.

A skilled builder could eliminate the PCB and use a breadboard with solder pads as well as a standard project box, but it will be a challenge — especially the mounting of the LCD display.

In reviewing the two programs that run this project, a lot more time could be spent on giving them more polish. No doubt programmers with more skill and artistic talent than I have could improve the overall appearance of the individual screens. The Internet radio portion of the code could also use some improvement, like displaying the radio station.

Inexpensive microcontrollers have completely changed the way digital clocks are designed. With the introduction of built-in wireless Internet in microcontrollers like the ESP32, another wave of changes in the design of digital clocks with added features is possible.

Given the program size available on both the ESP32 and Teensy 3.5, I suspect most of the ideas mentioned above could be programmed into this project without any hardware changes.

Along 3 years I have been trying several leg mechanism, at first I decided to do a simple desing with tibial motor where placed on femur joint.This design had several problems, like it wasn"t very robust and the most importat is that having the motor (with big mass) that far from the rotating axis, caused that in some movements it generate unwanted dynamics to the robot body, making controlability worse.New version have both motors of femur/tibial limb at coxa frame, this ends with a very simple setup and at the same time, the heaviest masses of the mechanism are centered to the rotating axis of coxa limb, so even though the leg do fast movements, inertias won"t be strong enough to affect the hole robot mass, achieving more agility.Inverse Kinematics of the mechanismAfter building it I notice that this mechanism was very special for another reason, at the domain the leg normally moves, it acts as a diferential mecanism, this means that torque is almost all the time shared between both motor of the longer limbs. That was an improvent since with the old mechanism tibial motor had to hold most of the weight and it was more forced than the one for femur.To visualize this, for the same movement, we can see how tibial motor must travel more arc of angel that the one on the new version.In order to solve this mechanism, just some trigonometry is needed. Combining both cosine and sine laws, we can obtain desired angle (the one between femur and tibia) with respect to the angle the motor must achieve.Observing these equations, with can notice that this angle (the one between femur and tibia) depends on both servos angles, which means both motors are contributing to the movement of the tibia.Calibration of servosAnother useful thing to do if we want to control servo precisely is to print a calibration tool for our set up. As shown in the image below, in order to know where real angles are located, angle protactor is placer just in the origin of the rotating joint, and choosing 2 know angles we can match PWM signal to the real angles we want to manipulate simply doing a lineal relation between angles and PWM pulse length.Then a simple program in the serial console can be wrtten to let the user move the motor to the desired angle. This way the calibration process is only about placing motor at certain position and everything is done and we won"t need to manually introduce random values that can be a very tedious task.With this I have achieved very good calibrations on motors, which cause the robot to be very simetrial making the hole system more predictable. Also the calibration procedure now is very easy to do, as all calculations are done automatically. Check Section 1 for the example code for calibration.More about this can be seen in the video below, where all the building process is shown as well as the new leg in action.SECTION 1:In the example code below, you can see how calibration protocol works, it is just a function called calibrationSecuence() which do all the work until calibration is finished. So you only need to call it one time to enter calibration loop, for example by sending a "c" character thought the serial console.Also some useful function are used, like moving motor directly with analogWrite functions which all the calculations involved, this is a good point since no interrupts are used.This code also have the feature to calibrate the potentiometer coming from each motor.#define MAX_PULSE 2500 #define MIN_PULSE 560 /*---------------SERVO PIN DEFINITION------------------------*/ int m1 = 6;//FR int m2 = 5; int m3 = 4; int m4 = 28;//FL int m5 = 29; int m6 = 36; int m7 = 3;//BR int m8 = 2; int m9 = 1; int m10 = 7;//BL int m11 = 24; int m12 = 25; int m13 = 0;//BODY /*----------------- CALIBRATION PARAMETERS OF EACH SERVO -----------------*/ double lowLim[13] = {50, 30, 30, 50, 30, 30, 50, 30, 30, 50, 30, 30, 70}; double highLim[13] = {130, 150, 150, 130, 150, 150, 130, 150, 150, 130, 150, 150, 110}; double a[13] = { -1.08333, -1.06667, -1.07778, //FR -1.03333, 0.97778, 1.01111, //FL 1.03333, 1.05556, 1.07778, //BR 1.07500, -1.07778, -1.00000, //BL 1.06250 }; double b[13] = {179.0, 192.0, 194.5, //FR 193.0, 5.5, -7.5, //FL 7.0, -17.0, -16.0, //BR -13.5, 191.5, 157.0, //BL -0.875 }; double ae[13] = {0.20292, 0.20317, 0.19904 , 0.21256, -0.22492, -0.21321, -0.21047, -0.20355, -0.20095, -0.20265, 0.19904, 0.20337, -0.20226 }; double be[13] = { -18.59717, -5.70512, -2.51697, -5.75856, 197.29411, 202.72169, 185.96931, 204.11902, 199.38663, 197.89534, -5.33768, -32.23424, 187.48058 }; /*--------Corresponding angles you want to meassure at in your system-----------*/ double x1[13] = {120, 135, 90, 60, 135 , 90, 120, 135, 90, 60, 135, 90, 110}; //this will be the first angle you will meassure double x2[13] = {60, 90, 135, 120, 90, 135, 60, 90, 135, 120, 90, 135, 70};//this will be the second angle you will meassure for calibration /*--------You can define a motor tag for each servo--------*/ String motorTag[13] = {"FR coxa", "FR femur", "FR tibia", "FL coxa", "FL femur", "FL tibia", "BR coxa", "BR femur", "BR tibia", "BL coxa", "BL femur", "BL tibia", "Body angle" }; double ang1[13] = {0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0}; double ang2[13] = {0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0}; float xi[500]; float yi[500]; float fineAngle; float fineL; float fineH; int motorPin; int motor = 0; float calibrationAngle; float res = 1.0; float ares = 0.5; float bres = 1.0; float cres = 4.0; float rawAngle; float orawAngle; char cm; char answer; bool interp = false; bool question = true; bool swing = false; int i; double eang; int freq = 100; // PWM frecuency can be choosen here. void connectServos() { analogWriteFrequency(m1, freq); //FR coxa digitalWrite(m1, LOW); pinMode(m1, OUTPUT); analogWriteFrequency(m2, freq); //femur digitalWrite(m2, LOW); pinMode(m2, OUTPUT); analogWriteFrequency(m3, freq); //tibia digitalWrite(m3, LOW); pinMode(m3, OUTPUT); analogWriteFrequency(m4, freq); //FL coxa digitalWrite(m4, LOW); pinMode(m4, OUTPUT); analogWriteFrequency(m5, freq); //femur digitalWrite(m5, LOW); pinMode(m5, OUTPUT); analogWriteFrequency(m6, freq); //tibia digitalWrite(m6, LOW); pinMode(m6, OUTPUT); analogWriteFrequency(m7, freq); //FR coxa digitalWrite(m7, LOW); pinMode(m7, OUTPUT); analogWriteFrequency(m8, freq); //femur digitalWrite(m8, LOW); pinMode(m8, OUTPUT); analogWriteFrequency(m9, freq); //tibia digitalWrite(m9, LOW); pinMode(m9, OUTPUT); analogWriteFrequency(m10, freq); //FR coxa digitalWrite(m10, LOW); pinMode(m10, OUTPUT); analogWriteFrequency(m11, freq); //femur digitalWrite(m11, LOW); pinMode(m11, OUTPUT); analogWriteFrequency(m12, freq); //tibia digitalWrite(m12, LOW); pinMode(m12, OUTPUT); analogWriteFrequency(m13, freq); //body digitalWrite(m13, LOW); pinMode(m13, OUTPUT); } void servoWrite(int pin , double angle) { float T = 1000000.0f / freq; float usec = float(MAX_PULSE - MIN_PULSE) * (angle / 180.0) + (float)MIN_PULSE; uint32_t duty = int(usec / T * 4096.0f); analogWrite(pin , duty); } double checkLimits(double angle , double lowLim , double highLim) { if ( angle >= highLim ) { angle = highLim; } if ( angle <= lowLim ) { angle = lowLim; } return angle; } int motorInfo(int i) { enc1 , enc2 , enc3 , enc4 , enc5 , enc6 , enc7 , enc8 , enc9 , enc10 , enc11 , enc12 , enc13 = readEncoders(); if (i == 0) { rawAngle = enc1; motorPin = m1; } else if (i == 1) { rawAngle = enc2; motorPin = m2; } else if (i == 2) { rawAngle = enc3; motorPin = m3; } else if (i == 3) { rawAngle = enc4; motorPin = m4; } else if (i == 4) { rawAngle = enc5; motorPin = m5; } else if (i == 5) { rawAngle = enc6; motorPin = m6; } else if (i == 6) { rawAngle = enc7; motorPin = m7; } else if (i == 7) { rawAngle = enc8; motorPin = m8; } else if (i == 8) { rawAngle = enc9; motorPin = m9; } else if (i == 9) { rawAngle = enc10; motorPin = m10; } else if (i == 10) { rawAngle = enc11; motorPin = m11; } else if (i == 11) { rawAngle = enc12; motorPin = m12; } else if (i == 12) { rawAngle = enc13; motorPin = m13; } return rawAngle , motorPin; } void moveServos(double angleBody , struct vector anglesServoFR , struct vector anglesServoFL , struct vector anglesServoBR , struct vector anglesServoBL) { //FR anglesServoFR.tetta = checkLimits(anglesServoFR.tetta , lowLim[0] , highLim[0]); fineAngle = a[0] * anglesServoFR.tetta + b[0]; servoWrite(m1 , fineAngle); anglesServoFR.alpha = checkLimits(anglesServoFR.alpha , lowLim[1] , highLim[1]); fineAngle = a[1] * anglesServoFR.alpha + b[1]; servoWrite(m2 , fineAngle); anglesServoFR.gamma = checkLimits(anglesServoFR.gamma , lowLim[2] , highLim[2]); fineAngle = a[2] * anglesServoFR.gamma + b[2]; servoWrite(m3 , fineAngle); //FL anglesServoFL.tetta = checkLimits(anglesServoFL.tetta , lowLim[3] , highLim[3]); fineAngle = a[3] * anglesServoFL.tetta + b[3]; servoWrite(m4 , fineAngle); anglesServoFL.alpha = checkLimits(anglesServoFL.alpha , lowLim[4] , highLim[4]); fineAngle = a[4] * anglesServoFL.alpha + b[4]; servoWrite(m5 , fineAngle); anglesServoFL.gamma = checkLimits(anglesServoFL.gamma , lowLim[5] , highLim[5]); fineAngle = a[5] * anglesServoFL.gamma + b[5]; servoWrite(m6 , fineAngle); //BR anglesServoBR.tetta = checkLimits(anglesServoBR.tetta , lowLim[6] , highLim[6]); fineAngle = a[6] * anglesServoBR.tetta + b[6]; servoWrite(m7 , fineAngle); anglesServoBR.alpha = checkLimits(anglesServoBR.alpha , lowLim[7] , highLim[7]); fineAngle = a[7] * anglesServoBR.alpha + b[7]; servoWrite(m8 , fineAngle); anglesServoBR.gamma = checkLimits(anglesServoBR.gamma , lowLim[8] , highLim[8]); fineAngle = a[8] * anglesServoBR.gamma + b[8]; servoWrite(m9 , fineAngle); //BL anglesServoBL.tetta = checkLimits(anglesServoBL.tetta , lowLim[9] , highLim[9]); fineAngle = a[9] * anglesServoBL.tetta + b[9]; servoWrite(m10 , fineAngle); anglesServoBL.alpha = checkLimits(anglesServoBL.alpha , lowLim[10] , highLim[10]); fineAngle = a[10] * anglesServoBL.alpha + b[10]; servoWrite(m11 , fineAngle); anglesServoBL.gamma = checkLimits(anglesServoBL.gamma , lowLim[11] , highLim[11]); fineAngle = a[11] * anglesServoBL.gamma + b[11]; servoWrite(m12 , fineAngle); //BODY angleBody = checkLimits(angleBody , lowLim[12] , highLim[12]); fineAngle = a[12] * angleBody + b[12]; servoWrite(m13 , fineAngle); } double readEncoderAngles() { enc1 , enc2 , enc3 , enc4 , enc5 , enc6 , enc7 , enc8 , enc9 , enc10 , enc11 , enc12 , enc13 = readEncoders(); eang1 = ae[0] * enc1 + be[0]; eang2 = ae[1] * enc2 + be[1]; eang3 = ae[2] * enc3 + be[2]; eang4 = ae[3] * enc4 + be[3]; eang5 = ae[4] * enc5 + be[4]; eang6 = ae[5] * enc6 + be[5]; eang7 = ae[6] * enc7 + be[6]; eang8 = ae[7] * enc8 + be[7]; eang9 = ae[8] * enc9 + be[8]; eang10 = ae[9] * enc10 + be[9]; eang11 = ae[10] * enc11 + be[10]; eang12 = ae[11] * enc12 + be[11]; eang13 = ae[12] * enc13 + be[12]; return eang1 , eang2 , eang3 , eang4 , eang5 , eang6 , eang7 , eang8 , eang9 , eang10 , eang11 , eang12 , eang13; } void calibrationSecuence( ) { //set servos at their middle position at firstt for (int i = 0; i <= 12; i++) { rawAngle , motorPin = motorInfo(i); servoWrite(motorPin , 90); } // sensorOffset0 = calibrateContacts(); Serial.println(" "); Serial.println("_________________________________SERVO CALIBRATION ROUTINE_________________________________"); Serial.println("___________________________________________________________________________________________"); Serial.println("(*) Don"t send several caracter at the same time."); delay(500); Serial.println(" "); Serial.println("Keyboard: "x"-> EXIT CALIBRATION. "c"-> ENTER CALIBRATION."); Serial.println(" "i"-> PRINT INFORMATION. "); Serial.println(" "); Serial.println(" "n"-> CHANGE MOTOR (+). "b" -> CHANGE MOTOR (-)."); Serial.println(" "m"-> START CALIBRATION."); Serial.println(" "q"-> STOP CALIBRATION."); Serial.println(" "); Serial.println(" "r"-> CHANGE RESOLUTION."); Serial.println(" "p"-> ADD ANGLE. "o"-> SUBTRACT ANGLE. "); Serial.println(" "s"-> SAVE ANGLE."); delay(500); Serial.println(" "); Serial.println("---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------"); Serial.print("SELECTED MOTOR: "); Serial.print(motorTag[motor]); Serial.print(". SELECTED RESOLUTION: "); Serial.println(res); while (CAL == true) { if (Serial.available() > 0) { cm = Serial.read(); if (cm == "x") { Serial.println("Closing CALIBRATION program..."); CAL = false; secuence = false; startDisplay(PAGE); angleBody = 90; anglesIKFR.tetta = 0.0; anglesIKFR.alpha = -45.0; anglesIKFR.gamma = 90.0; anglesIKFL.tetta = 0.0; anglesIKFL.alpha = -45.0; anglesIKFL.gamma = 90.0; anglesIKBR.tetta = 0.0; anglesIKBR.alpha = 45.0; anglesIKBR.gamma = -90.0; anglesIKBL.tetta = 0.0; anglesIKBL.alpha = 45.0; anglesIKBL.gamma = -90.0; } else if (cm == "i") { // + Serial.println(" "); Serial.println("---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------"); Serial.println("---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------"); Serial.println("(*) Don"t send several caracter at the same time."); delay(500); Serial.println(" "); Serial.println("Keyboard: "x"-> EXIT CALIBRATION. "c"-> ENTER CALIBRATION."); Serial.println(" "i"-> PRINT INFORMATION. "); Serial.println(" "); Serial.println(" "n"-> CHANGE MOTOR (+). "b" -> CHANGE MOTOR (-)."); Serial.println(" "m"-> START CALIBRATION."); Serial.println(" "q"-> STOP CALIBRATION."); Serial.println(" "); Serial.println(" "r"-> CHANGE RESOLUTION."); Serial.println(" "p"-> ADD ANGLE. "o"-> SUBTRACT ANGLE. "s"-> SAVE ANGLE."); Serial.println(" "); delay(500); Serial.println(" "); Serial.println("---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------"); Serial.println(" "); Serial.print("SELECTED MOTOR: "); Serial.print(motorTag[motor]); Serial.print(". SELECTED RESOLUTION: "); Serial.println(res); Serial.println("Actual parameters of the motor: "); Serial.print("High limit: "); Serial.print(highLim[motor]); Serial.print(" Low limit: "); Serial.print(lowLim[motor]); Serial.print(" Angle 1: "); Serial.print(ang1[motor]); Serial.print(" Angle 2: "); Serial.println(ang2[motor]); Serial.println("---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------"); } else if (cm == "m") { // + secuence = true; } else if (cm == "s") { // + } else if (cm == "n") { // + motor++; if (motor >= 13) { motor = 0; } Serial.print("SELECTED MOTOR: "); Serial.println(motorTag[motor]); } else if (cm == "b") { // + motor--; if (motor < 0) { motor = 13 - 1; } Serial.print("SELECTED MOTOR: "); Serial.println(motorTag[motor]); } else if (cm == "r") { // + if (res == ares) { res = bres; } else if (res == bres) { res = cres; } else if (res == cres) { res = ares; } Serial.print("SELECTED RESOLUTION: "); Serial.println(res); } } if (secuence == true) { Serial.print("Starting secuence for motor: "); Serial.println(motorTag[motor]); for (int i = 0; i <= 30; i++) { delay(20); Serial.print("."); } Serial.println("."); while (question == true) { unsigned long currentMicros = micros(); if (currentMicros - previousMicros >= 100000) { previousMicros = currentMicros; if (Serial.available() > 0) { answer = Serial.read(); if (answer == "y") { question = false; interp = true; secuence = true; } else if (answer == "n") { question = false; interp = false; secuence = true; } else { Serial.println("Please, select Yes(y) or No(n)."); } } } } answer = "t"; question = true; if (interp == false) { Serial.println("___"); Serial.println(" | Place motor at 1ts position and save angle"); Serial.println(" | This position can be the higher one"); rawAngle , motorPin = motorInfo(motor); calibrationAngle = 90; //start calibration at aproximate middle position of the servo. while (secuence == true) { /* find first calibration angle */ if (Serial.available() > 0) { cm = Serial.read(); if (cm == "p") { // + Serial.print(" | +"); Serial.print(res); Serial.print(" : "); calibrationAngle = calibrationAngle + res; servoWrite(motorPin , calibrationAngle); Serial.println(calibrationAngle); } else if (cm == "o") { // - Serial.print(" | -"); Serial.print(res); Serial.print(" : "); calibrationAngle = calibrationAngle - res; servoWrite(motorPin , calibrationAngle); Serial.println(calibrationAngle); } else if (cm == "r") { // + if (res == ares) { res = bres; } else if (res == bres) { res = cres; } else if (res == cres) { res = ares; } Serial.print("SELECTED RESOLUTION: "); Serial.println(res); } else if (cm == "q") { // quit secuence secuence = false; Serial.println(" | Calibration interrupted!!"); } else if (cm == "s") { // save angle ang1[motor] = calibrationAngle; secuence = false; Serial.print(" | Angle saved at "); Serial.println(calibrationAngle); } } } if (cm == "q") { Serial.println(" |"); } else { secuence = true; Serial.println("___"); Serial.println(" | Place motor at 2nd position and save angle"); Serial.println(" | This position can be the lower one"); } while (secuence == true) { /* find second calibration angle */ if (Serial.available() > 0) { cm = Serial.read(); if (cm == "p") { // + Serial.print(" | +"); Serial.print(res); Serial.print(" : "); calibrationAngle = calibrationAngle + res; servoWrite(motorPin , calibrationAngle); Serial.println(calibrationAngle); } else if (cm == "o") { // - Serial.print(" | -"); Serial.print(res); Serial.print(" : "); calibrationAngle = calibrationAngle - res; servoWrite(motorPin , calibrationAngle); Serial.println(calibrationAngle); } else if (cm == "r") { // + if (res == ares) { res = bres; } else if (res == bres) { res = cres; } else if (res == cres) { res = ares; } Serial.print("SELECTED RESOLUTION: "); Serial.println(res); } else if (cm == "q") { // quit secuence secuence = false; Serial.println(" | Calibration interrupted!!"); } else if (cm == "s") { // save angle ang2[motor] = calibrationAngle; secuence = false; Serial.print(" | Angle saved at "); Serial.println(calibrationAngle); } } } /*--------------------start calibration calculations------------------*/ if (cm == "q") { Serial.println("___|"); Serial.println("Calibration finished unespected."); Serial.println(" Select another motor."); Serial.print("SELECTED MOTOR: "); Serial.print(motorTag[motor]); Serial.print(". SELECTED RESOLUTION: "); Serial.println(res); } else { Serial.println("___"); Serial.println(" |___"); Serial.print( " | | Interpolating for motor: "); Serial.println(motorTag[motor]); secuence = true; //real angle is calculated interpolating both angles to a linear relation. a[motor] = (ang2[motor] - ang1[motor]) / (x2[motor] - x1[motor]); b[motor] = ang1[motor] - x1[motor] * (ang2[motor] - ang1[motor]) / (x2[motor] - x1[motor]); Serial.println(" | |"); } interp = true; } /*---------------------------make swing movement to interpolate motor encoder-----*/ if (interp == true and secuence == true) { delay(200); double x; int k = 0; int stp = 180; swing = true; i = 0; orawAngle , motorPin = motorInfo(motor); previousMicros = 0; while (swing == true) { // FIRST unsigned long currentMicros = micros(); if (currentMicros - previousMicros >= 10000) { // save the

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey