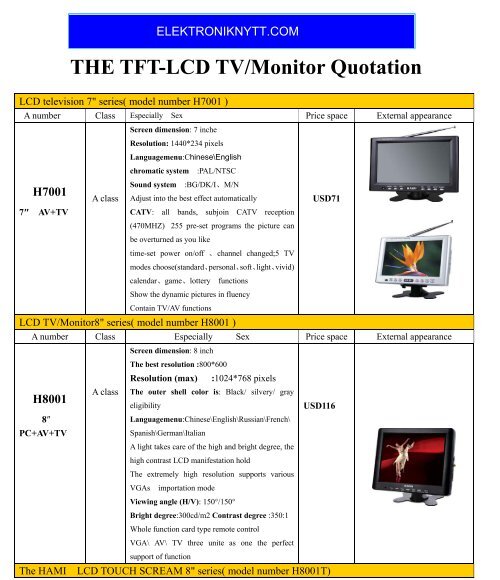

tft lcd pixel size quotation

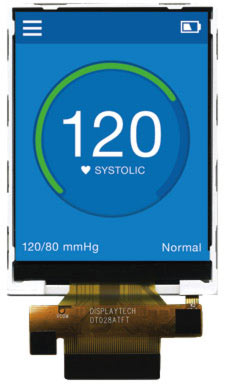

Looking for a specific TFT resolution? We offer LCD TFTs varying in resolution from 128x160 pixels to 800x480 pixels. Many of our TFT LCDs also have carrier boards to make integrating them into your product as simple as possible. All of our TFT LCDs offer full color RGB. If you"re not finding the correct TFT LCD for your product or project, please contact our support team to see if they can help you find an appropriate TFT display module for you.

The provided display driver example code is designed to work with Microchip, however it is generic enough to work with other micro-controllers. The code includes display reset sequence, initialization and example PutPixel() function.

Please see the DT028CTFT for reference designs. The schematics between the A and the C are the same with the exception that the A does not have the IPS interface.

Showcase high quality graphics and images on our 800 x 480 7” TFT display! The DT070CTFT LCD module is an upgraded version to our DT070ATFT module. Compared to the previous model, this new 7 inch display offers improved viewing angle and brighter LEDs. The DT070CTFT also uses the Himax HX8264E + HX8664B display drivers. This LCD display is available with a resistive or capacitive touchscreen panel.

TFT displays are full color LCDs providing bright, vivid colors with the ability to show quick animations, complex graphics, and custom fonts with different touchscreen options. Available in industry standard sizes and resolutions. These displays come as standard, premium MVA, sunlight readable, or IPS display types with a variety of interface options including HDMI, SPI and LVDS. Our line of TFT modules include a custom PCB that support HDMI interface, audio support or HMI solutions with on-board FTDI Embedded Video Engine (EVE2).

This 240x320 resolution LCD TFT is a standard display with 8-bit/16-bit Parallel interface, offering 262K colors and a 6:00 optimal view. This Liquid Crystal Display has a built-in ST7789Vi controller, FFC ZIF I/O connection, is RoHS compliant and does not come with a touchscreen.

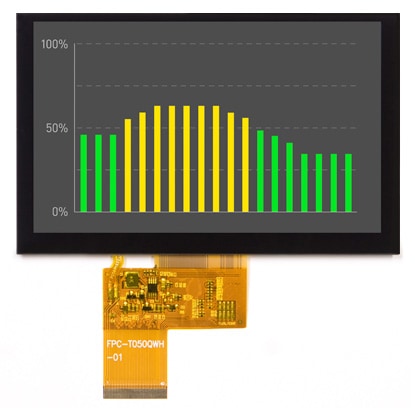

ER-TFT050-3 is 800x480 dots 5" color tft lcd module display with ILI6122 driver IC,optional 5 points capacitive multi-touch panel with controller GSL1680 and optional 4-wire resistive touch panel screen,superior display quality,super wide view angle and easily controlled by MCU such as 8051, PIC, AVR, ARDUINO, ARM and Raspberry PI.

Our advanced, feature-rich TFT displays offer you the very latest solutions to meet the demands of any project. With exceptional resolution, brightness and contrast, optimum readability and performance in all environments, and wide viewing angles, our TFTs also come with optional Projective Capacitive Touch (PCT)read more...

Range of small to medium sized TFT panels (3.5, 4.3 & 5.7 with and without Touch Panel) suitable for medical equipments, T&M equipment and telecom/ consumer equipments.

Varitronix provide a range of industrial and consumer grade small to medium sized TFT panels. They are suitable for a multitude of applications from navigation systems and test and measurement equipment to digital signage and consumer products. Our displays are available with an analogue or digital interface and are semi orread more...

Products»All Products»Power & UPS»Batteries & Ultracapacitors»Standard DC-DC Power»Smart DC-DC Power»Smart Battery Chargers»Galvanically Isolated Power Supplies»24V Output Supplies»Ultracapacitor Chargers»Adjustable Output Power Supplies»Universal Chargers»Uninterruptible Power Supplies»Embedded Boards»I/O & Communication»Embedded CAN bus Modules»Embedded Ethernet Switches»Embedded Digital IO Modules»Embedded Analog IO Modules»Embedded Serial IO Modules»PCIe Mini Cards»Embedded Power Supplies»Standard Embedded Power»Smart Embedded Power»PC/104 Power Supplies»Embedded UPS Modules»Embedded Motherboards»PC/104 Motherboards»ETX Motherboards»COM Express Motherboards»EPIC Motherboards»EBX Motherboards»Mini-ITX Motherboards»Micro-ATX Motherboards»Industrial ATX Motherboards»Embedded GPS Modules»GPS Receiver Modules»Embedded GPS Antennas»CPU Boards & SBC»PC/104 SBC»EPIC SBC»ETX SBC»EBX SBC»Mini-ITX SBC»ARM CPU Modules»Micro-ATX SBC»Embedded ATX SBC»Com Express SBC»Embedded Ultracapacitor Modules»Embedded Battery Modules»Embedded Video Cards»Systems»Fanless Box PC»Wide Temperature»Industrial Automation Computers»Rugged Vehicle Computers»Railway Computers»Vehicle Tracking Systems»Industrial Rackmount Computers»Wide Temperature Systems»Digital Displays»Marine Monitors»Rugged LCD Displays»Wide Temperature LCD Displays»Waterproof LCD Panels»Advertising LCD Displays»Stretched Bar LCD»Sunlight Readable LCD Displays»Public Transportation LCD Displays»Railway LCD Displays»Outdoor LCD Displays»High Brightness LCD Displays»Extended Temperature LCD Displays»Industrial Monitors»Panel Computing»Marine Panel PC»Infotainment Panel PC»Wide Temperature Panel PC»HMI Panel PC»Modular Panel PC»Mobile Computing»Rugged Tablets»Rugged Windows Tablets»Rugged Android Tablets»Rugged PDA»Antennas»GPS Antennas»External GPS Antennas»Passive GPS Antennas»Active GPS Antennas»Marine GPS Antennas»Internal GPS Antennas»GNSS Antennas»GLONASS Antennas»Multi-Band Antennas»GPS-GLONASS Antennas»Iridium Antennas»GPS & RF Signal Distribution»GPS Amplifiers»Low Noise Amplifiers»GPS Receivers»Marine GPS Receivers»GPS Attenuators»GPS Combiners»GPS Splitters»Active GPS Splitters»Military GPS Splitters»Rackmount GPS Splitters»Passive GPS Splitters»Repeaters»GPS Repeaters»GLONASS Repeaters»GPS Filters»Enclosures & Chassis»PC/104 Chassis»Rugged Mini-ITX Cases»EPIC Enclosures»EBX Enclosures»Memory & Storage»Memory»Flash Storage»Industrial SSD»SATA Disk On Modules»Industrial Micro SD Cards»Industrial SD Cards»Industrial CompactFlash Cards»Sensors»Industrial Networking»Manufactured by Tri-M»Power & UPS»Standard Power Supplies»HE104: 60 Watt»HE104-DX: 60 Watt»HE104-75W: 75 Watt»HE104+DX: 108 Watt»HE-HP: 100 Watt»Smart Power Supplies (PowerOS)»HESC-SERD: 60 Watt»HESC104+: 108 Watt»HPS3512: 203 Watt»HPSP-XYZ: 240W Programmable»V12SC-SER[-UPS]»TPS1000: 35 Watt, 42 Watt»TPSi1075: 75 Watt, Isolated»TPSi1085: 85 Watt, Isolated»HPSC104-SER: 160 Watt»HESC104: 60 Watt»TPS1035»TPC1000»HPS3524»Smart UPS (PowerOS)»TUP1000: Ultracapacitor UPS»V5SC-SER-UPS: NiMh Battery UPS»UltraUPS»V12SC-SER[-UPS]»Ultra Capacitor Packs»TBP4xxx»Battery Backup Packs»BAT-NiMh45»BAT104-NiMh»BAT104-NiCd»BAT-SLA(25/45)»UltraUPS»Heavy Duty Transient Stopper»CPU Modules»I/O & Communication»Input / Output»IO104-60IN: PC104 I/O Board»IR104 PC/104 Relay Module»Communication»TCB1000 PC/104 Com Board»FlexCom104-GPS»Enclosures»VersaTainer: PC104 & EBX»CanTainer: PC104»FlexTainer: EPIC, MITX, EBX»GPS & Networking»GPS & Networking Boards»FlexCom104-GPS»Antennas»Mighty Mouse: Small GPS Antenna»Micro Mouse: Micro GPS Antenna»Big Brother»Re-Radiators»Super-Radiator»Xtreme-Radiator»Vehicle GPS Repeater»Complete System Solutions»HECS1000 System»UltraUPS Complete Backup Solution»Support Products & Accessories»PC104-T AC Termination Modules»Extract104»TS-I2C Temperature Sensor»DA104»VSX-2812 Video Modules»ISA104X1»Postcode104»Legacy Products»Distributed by Tri-M»Diamond Systems»Single Board Computers»Aurora PC/104 SBC»Helios PC/104 SBC»Neptune EPIC SBC»Pluto ETX SBC»Hercules III EBX SBC»IEI»IEI Mobile»MicroMax Computer Intelligence»San Jose Technology (SANAV)»GNSS Repeaters»RK-306»RK-106»Innodisk»GPS Networking»Litemax»Spanpixel»Durapixel»Navpixel»Aaeon Electronics»Systems»Fanless Embedded Computers»Entry-Level Box PC»ICOP Technology»ICOP-2811»VDX2-6554»VEX-6254»VSX-2812S»86Duino Enjoy Desktop 3D Printer»MPLSelector Guides»Power Selector Guide»Backup Power SelectorServices»Conformal Coating»HumiSeal 1B31»Laser Engraving & EtchingTri-M Rugged»PowerOS»Mining Applications»Mining Application Story»Rail & ITS Applications»Automation & Manufacturing»Mil-Aero Defence & Aerospace»Aerospace Application StorySupportAbout Us»About Us»Privacy PolicywebstoreTriple Programmable PSUQuote Request

The liquid crystal display (LCD) technology has been used in several electronic products over the years. There are more reasons for LCDs to be more endearing than CRTs.

LCD stands for “Liquid Crystal Display” and TFT stands for “Thin Film Transistor”. These two terms are used commonly in the industry but refer to the same technology and are really interchangeable when talking about certain technology screens. The TFT terminology is often used more when describing desktop displays, whereas LCD is more commonly used when describing TV sets. Don’t be confused by the different names as ultimately they are one and the same. You may also see reference to “LED displays” but the term is used incorrectly in many cases. The LED name refers only to the backlight technology used, which ultimately still sits behind an liquid crystal panel (LCD/TFT).

As TFT screens are measured differently to older CRT monitors, the quoted screen size is actually the full viewable size of the screen. This is measured diagonally from corner to corner. TFT displays are available in a wide range of sizes and aspect ratios now. More information about the common sizes of TFT screens available can be seen in our section about resolution.

The aspect ratio of a TFT describes the ratio of the image in terms of its size. The aspect ratio can be determined by considering the ratio between horizontal and vertical resolution.

The resolution of a TFT is an important thing to consider. All TFT’s have a certain number of pixels making up their liquid crystal matrix, and so each TFT has a “native resolution” which matches this number. It is always advisable to run the TFT at its native resolution as this is what it is designed to run at and the image does not need to be stretched or interpolated across the pixels. This helps keep the image at its most clear and at optimum sharpness. Some screens are better than others at running below the native resolution and interpolating the image which can sometimes be useful in games.

You generally cannot run a TFT at a resolution of above its native resolution although some screens have started to offer “Virtual” resolutions, for example “virtual 4k” where the screen will accept a 3840 x 2160 input from your graphics card but scale it back to match the native resolution of the panel which is often 2560 x 1440 in these examples. This whole process is rather pointless though as you lose a massive amount of image quality in doing so.

Ultra-high resolutions must be thought of in a slightly different way. Ultra HD (3840 x 2160) and 4K (4096 x 2160) resolutions are being provided nowadays on standard screen sizes like 24 – 27” for instance. Traditionally as you increased the resolution of panels it was about providing more desktop real estate to work with. However, with those resolutions being so high, and the screen size being relatively small still, the image and text becomes incredibly small if you run the screen at normal scaling at those native resolutions. For instance imagine a 3840 x 2160 resolution on a 24” screen compared with 1920 x 1080. The latter would probably be considered a comfortable font size for most users. These ultra-high resolutions nowadays are about improving image clarity and sharpness, and providing a higher pixel density (measured as pixels per inch = PPI). In doing so, you can improve the sharpness and clarity of an image much like Apple have famously done with their “Retina” displays on iPads and iPhones. To avoid complications with tiny images and fonts, you will then need to enable scaling in your operating system to make everything easier to see. For instance if you enabled scaling at 150% on a 3840 x 2160 resolution, you would end up with a screen real estate equivalent to a 2560 x 1440 panel (3840 / 1.5 = 2560 and 2160 / 1.5 = 1440). This makes text much easier to read and the whole image a more comfortable size, but you then get additional benefits from the higher pixel density instead, which results in a sharper and crisper image.

Generally you will need to take scaling in to consideration when purchasing any ultra-high resolution screen, unless it’s of a very large size. The scaling ability does vary however between different operating systems so be careful. Apple OS and modern Windows (8 and 10) are generally very good at handling scaling for ultra-high res displays. Older operating systems are less capable and may sometimes be complicated. You will also find varying support from different applications and games, and often end up with weird sized fonts or sections that are not scaled up and remain extremely small. A “standard” resolution where you don’t need to worry about scaling might be simpler for most users.

More and more you will see resolutions referred to by their common HD equivalents, particularly when it comes to TV’s. HD content is based purely on the resolution of the source and is commonly defined by the number of pixels vertically in the resolution. i.e. a 720 HD source has 720 vertical pixels in it’s resolution and a 1080 will have 1080. On top of this, there are two ways of showing this content, either using a progressive scan (e.g. 1080p) or an interlaced scan (1080i).

To display this content of this type, your screen needs to be able to 1) handle the full resolution naturally within its native resolution, and 2) be able to handle either the progressive scan or interlaced signal over whatever video interface you are using. If the screen cannot support the full resolution, the image can still be shown but it will be scaled down by the hardware and you won’t be take full advantage of the high resolution content. So for a monitor, if you want to watch 1080 HD content you will need a monitor which can support at least a vertical resolution of 1080 pixels, e.g. a 1920 x 1080 monitor.

In today’s monitor market resolutions are being pushed even higher and we need to start thinking about them in a different way. See the subsequent sections on pixel pitch and PPI for more information on how we should think about resolution now.

This has given rise to modern Ultra HD standards and terms like 4K and 5K. Ultra HD is a term for monitors with a 3840 x 2160 resolution, that being four times the resolution of Full HD 1920 x 1080. Screens with this Ultra HD resolution are often referred to as “4K” as well, although strictly that should only be used for screens with 4092 x 2160 resolution (4K representing the vertical resolution here). There are also some 5K capable monitors produced which offer 5120 x 2880 resolution (5K here representing the vertical resolution). Please see the following sections which talk about Pixel Pitch and PPI and will help you understand these higher resolutions in more detail.

Unlike on CRT’s where the dot pitch is related to the sharpness of the image, the pixel pitch of a TFT is related to the distance between pixels. This value is fixed and is determined by the size of the screen and the native resolution (number of pixels) offered by the panel. Pixel pitch is normally listed in the manufacturers specification. Generally you need to consider that the ‘tighter’ the pixel pitch, the smaller the text will be, and potentially the sharper the image will be. To be honest, monitors are normally produced with a sensible resolution for their size and so even the largest pixel pitches return a sharp images and a reasonable text size. Some people do still prefer the larger-resolution-crammed-into-smaller-screen option though, giving a smaller pixel pitch and smaller text. It’s down to choice and ultimately eye-sight.

For instance you might see a 35″ ultra-wide screen with only a 2560 x 1080 resolution which would have a 0.3200 mm pixel pitch. Compare this to a 25″ screen with 2560 x 1400 resolution and 0.2162 mm pixel pitch and you can see there will be a significant different in font size and image sharpness. There are further considerations when it comes to the pixel pitch of ultra-high resolution displays like Ultra HD and 4K. See the section on PPI for more information.

Resolution is typically thought as a factor which determines the screen area or screen “real estate” you will have available. In years gone by as panel sizes increased, resolutions were increased as well and so bigger screens could offer you more desktop space to work with. Split-screen working and high resolution image work become more and more possible. This is fine up to a point, but pushing resolution for the purposes of delivering more desktop real-estate reaches a point where it becomes somewhat impractical for desktop monitors. For instance, a 40″ 3840 x 2160 resolution delivers a comfortable pixel pitch and font size natively (very similar to a 27″ at 2560 x 1440), so if you wanted a higher resolution than this you would have to increase the screen size again probably. You start to reach the point where sitting close to a screen so large becomes impractical.

Instead manufacturers are now focusing on delivering higher resolutions in to existing panel sizes, not for the purpose of providing more desktop real-estate, but for the purpose of improving image sharpness and picture quality. Apple started this trend with their “Retina Displays” used in iPads and iPhones, improving image sharpness and clarity massively. It is common now to see smaller screens such as 24″ and 27″ for instance, but with high resolutions like 3840 x 2160 (Ultra HD) or even 5120 x 2880 (5K). By packing more pixels in to the same screen size which would typically offer a 2560 x 1440 resolution, panel manufacturers are able to provide much smaller pixel pitches and improve picture sharpness and clarity. To measure this new way of looking at resolution you will commonly see the spec of ‘Pixels Per Inch’ (PPI) being used.

Of course the problem with this is that if you run a screen as small as 27″ with a 5K resolution, the font size is absolutely tiny by default. You get a massive boost of desktop real-estate, just like when moving from 1920 x 1080 to 2560 x 1440, but that’s not the purpose of these higher resolutions now. To overcome this you need to use the scaling options in your Operating System software to scale the image and make it more usable. Windows provides for instance scaling options like 125% and 150% within the control panel. On a 3840 x 2160 Ultra HD resolution if you use a 150% scaling option for example you will in effect reduce the desktop area by a third, resulting in the same desktop area as a 2560 x 1440 display (i.e. 2560 x 150% = 3840). The OS scaling makes font sizes more comfortable and reasonable, but you maintain the sharp picture quality and small pixel pitch of the higher resolution panel. A 3840 x 2160 res panel scaled at 150% in Windows will look sharper and crisper than a 2560 x 1440 native panel without scaling, despite the fact both would have the same effective desktop area available.

Scaling via your OS is not the same as scaling from your monitor. If you just simply ran the screen at a lower resolution like 2560 x 1440 within the resolution section of your graphics card, the image gets interpolated by the monitor scaler instead. You get the same end result of a 2560 x 1440 sized desktop area size, but the image clarity is lost and you lose a lot of sharpness. The monitor is doing the interpolation for you here. Instead you run the screen at the full 3840 x 2160 resolution in the graphics card settings and allow the OS scaling control to increase font size and make the image useable.

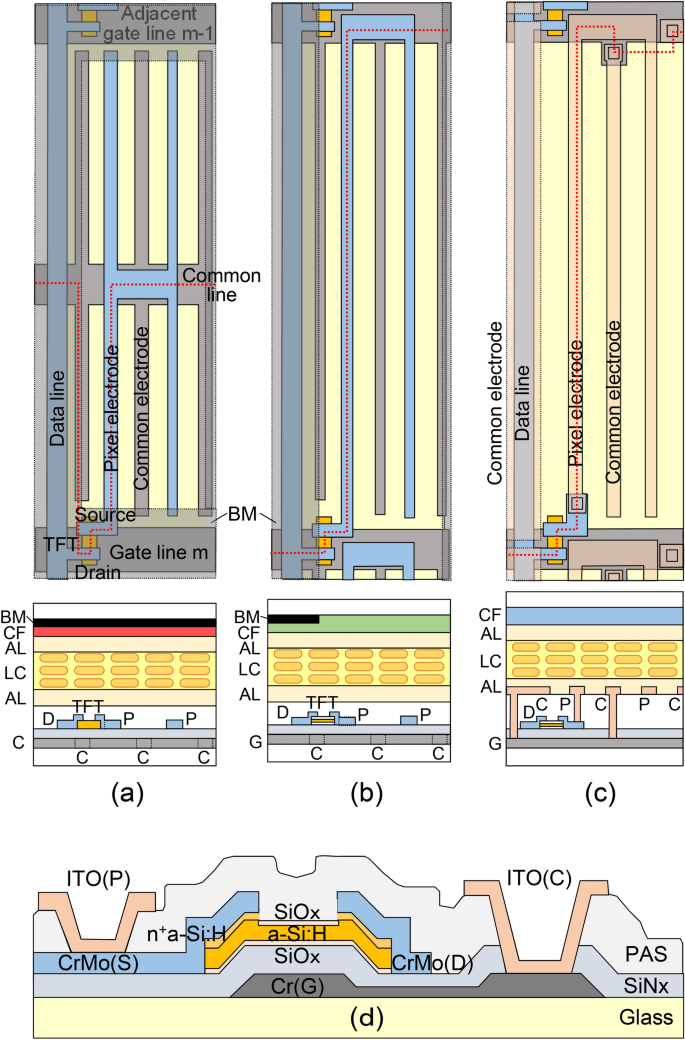

While this aspect is not always discussed by display manufacturers it is a very important area to consider when selecting a TFT monitor. The LCD panels producing the image are manufactured by many different panel vendors and most importantly, the technology of those panels varies. Different panel technologies will offer different performance characteristics which you need to be aware of. Their implementation is dependent on the panel size mostly as they vary in production costs and in target markets. The four main types of panel technology used in the desktop monitor market are:

TN Film was the first panel technology to be widely used in the desktop monitor market and is still regularly implemented in screens of all sizes thanks to its comparatively low production costs. TN Film is generally characterized by good pixel responsiveness making it a popular choice for gamer-orientated screens. Where overdrive technologies are also applied the responsiveness is improved further. TN Film panels are also available supporting 120Hz+ refresh rates making them a popular choice for stereoscopic 3D compatible screens. While older TN Film panels were criticized for their poor black depth and contrast ratios, modern panels are actually very good in this regard, often producing a static contrast ratio of up to 1000:1. Perhaps the main limitation with TN Film technology is its restrictive viewing angles, particularly in the vertical field. While specs on paper might look promising, in reality the viewing angles are restrictive and there are noticeable contrast and gamma shifts as you change your line of sight. TN Film panels are normally based around a 6-bit colour depth as well, with a Frame Rate Control (FRC) stage added to boost the colour palette. They are often excluded from higher end screens or by colour enthusiasts due to this lower colour depth and for their viewing angle limitations. TN Film panels are regularly used in general lower end and office screens due to cost, and are very popular in gaming screens thanks to their low response times and high refresh rate support. Pretty much all of the main panel manufacturers produce TN Film panels and all are widely used (and often interchanged) by the screen manufacturers.

IPS was originally introduced to try and improve on some of the drawbacks of TN Film. While initially viewing angles were improved, the panel technology was traditionally fairly poor when it came to response times and contrast ratios. Production costs were eventually reduced and the main investor in this technology has been LG.Display (formerly LG.Philips). The original IPS panels were developed into the so-called Super IPS (S-IPS) generation and started to be more widely used in mainstream displays. These were characterized by their good colour reproduction qualities, 8-bit colour depth (without the need for Frame Rate Control) and very wide viewing angles. These panels were traditionally still quite slow when it came to pixel response times however and contrast ratios were mediocre. In more recent years a change was made to the pixel alignment in these IPS panels (see our detailed panel technology article for more information) which gave rise to the so-called Horizontal-IPS (H-IPS) classification. With the introduction of overdrive technologies, response times were improved significantly, finally making IPS a viable choice for gaming. This has resulted more recently in IPS panels being often regarded as the best all-round technology and a popular choice for display manufacturers in today’s market. Improvements in energy consumption and reduced production costs lead to the generation of so-called e-IPS panels. Unlike normal 8-bit S-IPS and H-IPS classification panels, the e-IPS generation worked with a 6-bit + FRC colour depth. Developments and improvements with colour depths also gave rise to a generation of “10-bit” panels with some manufacturers inventing new names for the panels they were using, including the co-called Performance-IPS (p-IPS). It is important to understand that these different variants are ultimately very similar and the names are often interchanged by different display vendors. For more information, see our detailed panel technologies guide.

The original early VA panels were quickly scrapped due to their poor viewing angles, and in their place came the two main types of VA matrix. Multi-Domain Vertical Alignment (MVA) and Patterned Vertical Alignment (PVA) panels. These VA variants were characterized by their reasonably wide viewing angles, being better than TN Film but not as wide as IPS. They were originally poor when it came to pixel response times but offered 8-bit colour depths and the best static contrast ratios of all the technologies discussed here. Traditionally VA panels were capable of static contrast ratios of around 1000 – 1200:1 but this has even been improved now to 3000:1 and above. Until very recently VA panels remained very slow and so were not really suitable for gaming. However during 2012 we saw advancements with the latest generation of VA panels and through the use of overdrive technologies this has been significantly improved. Perhaps the main limitation with VA panels is still their viewing angles when compared with popular IPS panel options. Gamma and contrast shifts can be an issue and the technology also suffers from an inherent off-centre contrast shift issue which can be distracting to some users. Through the years we have seen several different generations of VA panels. AU Optronics are the main manufacturer of MVA matrices, and we have seen the so-called Premium-MVA (P-MVA) and Advanced-MVA (AMVA) generations emerge. Chi Mei Innolux (previously Chi Mei Optoelectronics / CMO) also make their own variant of MVA which they call Super-MVA (S-MVA).The only manufacturer of PVA panels is Samsung as it is their own version of VA technology. We have seen several generations from them including Super-PVA (S-PVA) and cPVAandSVA. For more information, see our detailed panel technologies guide.

This technology was developed by Sharp for use in some of their TFT displays. It consists of several improvements that Sharp claim to have made, mainly to counter the drawbacks of the popular TN Film technology. They have introduced an Anti-Glare / Anti-Reflection (AGAR) screen coating which forms a quarter-wavelength filter. Incident light is reflected back from front and rear surfaces 180° out of phase, thus canceling reflection rather diffusing it as others do. As well as reducing glare and reflection from the screen, this is marketed as being able to offer deeper black levels. Sharp also claim to offer better contrast ratios than any competing technology (VA and IPS); but with more emphasis on improving these other technologies, this is probably not the case with more modern panels. There are very few ASV monitors around really, with the majority of the market being dominated by TN, VA and IPS panels.

This technology was developed by BOE Hydis, and is not really very widely used in the desktop TFT market, more in the mobile and tablet sectors. It is worth mentioning however in case you come across displays using this technology. It was developed by BOE Hydis to offer improved brightness and viewing angles to their display panels and claims to be able to offer a full 180/180 viewing angle field as well as improved colours. This is basically just an advancements from IPS and is still based on In Plane technology. They claim to “modify pixels” to improve response times and viewing angles thanks to improved alignment. They have also optimised the use of the electrode surface (fringe field effect), removed shadowed areas between pixels, horizontally aligned electric fields and replaced metal electrodes with transparent ones. More information about AFFS can be found here.

This panel technology was developed by NEC LCD, and is reported to offer wide viewing angles, fast response times, high luminance, wide colour gamut and high definition resolutions. Of course, there is a lot of marketing speak in there, and the technology is not widely employed in the mainstream monitor market. Wide viewing angles are possible thanks to the horizontal alignment of liquid crystals when electrically charged. This alignment also helps keep response times low, particularly in grey to grey transitions. Their SFT range also offers high definition resolutions and are commonly used in medical displays where extra fine detail is required.

NEC’s SFT technology was first developed to be labelled as Advanced-SFT (A-SFT) which offered enhanced luminance figures. This then developed further to Super Advanced-SFT (SA-SFT) where colour gamut reached 72% of the NTSC colour space, and then to Ultra Advanced-SFT (UA-SFT) where the gamut was still at 72% or higher, but with a further enhancement of the luminance as compared with SA-SFT. These changes were all made possible thanks to the improved transmissivity of the SFT technology. More information is available from NEC LCD

Response Time is the spec which many people, especially gamers, have come to regard as the most important. In practical terms the spec is designed to refer to the speed of the liquid crystal pixels and how quickly they can change from one colour to another, and therefore how fast the picture can be redrawn. The faster this transition can change, the better, and with more fluid changes the images can change overall a lot faster. This helps reduce the effects of blurring and ghosting in games and movies which can be an issue if response time is too slow. As a general rule of thumb, the lower the response time, the better.

The traditional response time standard (ISO response time) is measured as the rise time (tR) and fall time (tF) of a pixel as it changes black > white > black. The total ‘response time’ is quoted as the total of the tR + tF. On older screens users needed to be wary of the figures manufacturers quote, as sometimes the ‘response time’ can be quoted as just the rise time, and not the total response time. This measurement of the black > white > black transition was defined as the ISO standard for response time measurements before the days of ‘overdrive’ being used (discussed in a moment). The reason this particular transition was selected as the response time figure was that it was always the fastest change possible, and manufacturers therefore quoted their best measurement. The reason this was the fastest was because at the time the highest voltage was applied to the pixels to make that change (since it was the most drastic difference from black to white).

On these older panels where overdrive was not being used, in reality the response time of the pixels will vary depending on the colour change they are making. In practice, a full black > white change is not common, and instead the pixel transitions are in shades of grey, and are then passed through the RGB colour filters. The speed of change will depend on the darkness of the transition, and traditionally (before overdrive) the transitions to lighter greys will be faster. Therefore, a manufacturers quoted response time does not necessarily mean that the speed of the pixels is the same for all the transitions. It is always a good idea to see if there are any third party measurements of response time for any given screen before considering how fast a panel really is in practice. Also take into account perceived response time measurements and comparisons between screens as we carry out in our reviews.

As you can see from the graph, the actual response time can vary quite considerably across the whole grey range, with some changes being much slower. This is the reason you cannot always rely on quoted specs to give an accurate representation of a screens actual pixel response performance. The quoted figures from manufacturers should be treated as a rough guide however to a panels response time, as generally there has been some improvements in the overall latency with the changes from 25ms > 16ms > 12ms > 8ms > 5ms panel generations for instance. The shape of the graph is likely to remain quite similar, but overall, the curve will probably be a little lower when comparing an 8ms to a 16ms for instance. Overall it won’t be twice as fast though.

One thing to note regarding pixel response time is that the overall performance of the TFT will also depend on the technology of the panel used. TN film panels offer response time graphs similar to that above, but screens based on traditional VA / IPSvariant panels can show response time graphs more like this (we are assuming for now non-overdriven panels):

Overdrive or ‘Response Time Compensation’ (RTC) is a technology which is designed to boost the response times of pixels across all transitions, with particular focus on improving the grey to grey changes which is the most important as those transitions are far more common in real-life uses. It is achieved by sending an over-voltage to the pixels to make them change orientation more quickly. While the full black > white change remains largely unchanged (since it already received the maximum voltage anyway), improvements across other transitions are often dramatic. With the introduction of overdriven panels the ISO point is not always the fastest transition any more, and so if a monitor has a response time quoted as “grey to grey / G2G” then you can be pretty certain it is using overdrive technology. The manufacturers still want to quote the fastest response time of their panel and show the improvements they have made though, but be wary of this change away from the ISO standard of quoting response times. The ISO response times have hit a wall really with TN Film stuck at 5 – 8ms, IPS stuck at around 16ms and MVA/PVA stuck at about 12ms. However, with the introduction of overdrive technologies, the more important grey to grey transitions are now significantly improved, and response times of 1 – 5ms G2G are now common place. These technologies have allow significant improvements in all panel technologies, but particularly in IPS and VA panels where response times were previously poor.

Some reviews sites including TFTCentral have access to advanced photosensor (photodiodе + low-noise operational amplifier) and oscilloscope measurement equipment which allows them to measure response time as detailed above. See our article about response times for more information on that method. Graphs showing response time according to their equipment are produced. Other sites rely on observed responsiveness to compare how well a panel can perform in practice and what a user might see in normal use. We think it is important to study both methods if possible to give a fuller picture of a panels performance. For visual tests TFTCentral uses a program called PixPerAn (developed by Prad.de) which is good for comparing monitor responsiveness with its series of tests. The favourite seems to be the moving car test as shown here:

In addition to pixel response time measurements and visual tests described above, it is also possible to capture the levels of blurring and smearing the human eye will experience on a display. This is achieved using a pursuit camera setup. They are simply cameras which follow the on-screen motion and are extremely accurate at measuring motion blur, ghosting and overdrive artefacts of moving images. Since they simulate the eye tracking motion of moving eyes, they can be useful in giving an idea of how a moving image appears to the end user. It is the blurring caused by eye tracking on continuously-displayed refreshes (sample-and-hold) that we are keen to analyse with this new approach. This is not pixel persistence caused by response times; but a different cause of display motion blur which cannot be captured using static camera tests. Low response times do have a positive impact on motion blur, and higher refresh rates also help reduce blurring to a degree. It does not matter how low response times are, or how high refresh rates are, you will still see motion blur from LCD displays under normal operation to some extent and that is what this section is designed to measure. Further technologies specifically designed to reduce perceived motion blur are required to eliminate the blur seen on these type of sample-and-hold displays which we will also look at.

For these tests we use the Blurbusters.com Ghosting Motion Test which is designed to be used with pursuit camera setups. The pursuit camera method is explained at BlurBusters. We carry out the tests at various refresh rates, with and without any Blur Reduction mode enabled. These UFO objects were moving horizontally at 960 pixels per second, at a frame rate matching refresh rate of the monitor.

These tests capture the kind of blurring you would see with the naked eye when tracking moving objects across the screen (example from the Asus ROG Swift PG279Q). As you increase the refresh rate the perceived blurring is reduced, as refresh rate has a direct impact on motion blur. It is not eliminated entirely due to the nature of the sample-and-hold LCD display and the tracking of your eyes. No matter how fast the refresh rate and pixel response times are, you cannot eliminate the perceived motion blur without other methods.Tests like the above would give you an idea of the kind of perceived motion blur range when using the particular screen without any bur reduction mode active.

On screens with blur reduction backlights it is possible to greatly reduce the perceived motion blur. With these blur reduction features enabled the backlight is strobed briefly, once per refresh, for low persistence.The brief backlight flash prevents tracking-based motion blur and the moving object is far easier to see when tracking it across the screen with your eyes (or by the pursuit camera). Normally these blur reduction modes lead to extremely little leftover ghosting caused by pixel transitions (virtually invisible to the human eye), since nearly all (>99%+) pixel transitions, including overdrive artefacts, are now kept unseen by the human eye, while the backlight is turned off between refreshes.

The Contrast Ratio of a TFT is the difference between the darkest black and the brightest white it is able to display. This is really defined by the pixel structure and how effectively it can let light through and block light out from the backlight unit. As a rule of thumb, the higher the contrast ratio, the better. The depth of blacks and the brightness of the whites are better with a higher contrast ratio. This is also referred to as the static contrast ratio.

When considering a TFT monitor, a contrast ratio of 1000:1 is pretty standard nowadays for TN Film and IPS-type panels. VA-type panels can offer static contrast ratios of 3000:1 and above which are significantly higher than other competing panel technologies.

Some technologies boast the ability to dynamically control contrast (Dynamic Contrast Ratio – DCR) and offer much higher contrast ratios which are incredibly high (millions:1 for instance!). Be wary of these specs as they are dynamic only, and the technology is not always very useful in practice. Traditionally, TFT monitors were said to offer poor black depth, but with the extended use of VA panels, the improvements from IPS and TN Film technology, and new Dynamic Contrast Control technologies, we are seeing good improvements in this area. Black point is also tied in to contrast ratio. The lower the black point, the better, as this will ensure detail is not lost in dark image when trying to distinguish between different shades.

Brightness as a specification is a measure of the brightest white the TFT can display, and is more accurately referred to as its luminance. Typically TFT’s are far too bright for comfortable use, and the On Screen Display (OSD) is used to turn the brightness setting down. Brightness is measure in cd/m2 (candella per metre squared). Note that the recommended brightness setting for a TFT screen in normal lighting conditions is 120 cd/m2. Default brightness of screens out of the box is regularly much higher so you need to consider whether the monitor controls afford you a decent adjustment range and the ability to reduce the luminance to a comfortable level based on your ambient lighting conditions. Different uses may require different brightness settings as well so it is handy when reviews record the luminance range possible from the screen as you adjust the brightness control from 100 to 0%.

The colour depth of a TFT panel is related to how many colours it can produce and should not be confused with colour space (gamut). The more colours available, the better the colour range can potentially be. Colour reproduction is also different however as this related to how reliably produced the colours are compared with those desired.

The colour depth of a panel is determined really by the number of possible orientations of each sub pixel (red, blue and green). These different orientations basically determine the different shade of grey (or colours when filtered in the specific way via RGB sub pixels) and the more “steps” between each shade, the more possible colours the panel can display.

At the lower end, TN Film panels are normally quite economical, and their sub pixels only have 64 possible orientations each, giving rise to a true colour depth of only 262,144 (i.e. 64 steps on each RGB = 64 x 64 x 64 = 18). This is also referred to commonly s 18-bit colour (i.e. 6 bits per RGB sub pixel = 6 + 6 + 6) This colour depth is pretty limited and so in order to reach 16 million colours and above, panel manufacturers commonly use two technologies: Dithering and Frame Rate Control (FRC). These terms are often interchanged, but strictly can mean different things. These technologies simulate other colours allowing the colour depth to improve to typically 16.2 million colours.

Spatial Dithering – The dithering method involves assigning appropriate colour values from the available colour palette to close-by pixels in such a way that it gives the impression of a new colour tone which otherwise could not have been created at all. In doing so, there complex mappings according to which the ground colours are mutually assigned, otherwise it could result in colour noise / dithering noise. Dithering can be used to allow 6-Bit panels, like TN Film, to show 16.2 million perceived colours. This can however sometimes be detectable to the user, and can result in chessboard like patterns being visible in some cases.

Other panel technologies however can offer more possible pixel orientations and therefore more steps between each shade. VA and IPS panels are traditionally capable of 256 steps for each RGB sub pixel, allowing for a possible 16.7 million colours (true 8-bit, without FRC). These are referred to as 8-bit panels with 24-bit colour (8-bit per sub pixel = 8 + 8 + 8 = 24). While most IPS and VA panels support 8-bit colour, modern IPS and VA panels do sometimes use 6-bit + FRC instead. See this news piece for further information.

Colour gamut in TFT monitors refers to the range of colours the screen is capable of displaying, and how much of a given reference colour space it might be able to display. It is ultimately linked to backlight technology and not to the panel itself.

Laser Displays are capable of producing the biggest colour gamut for a system with three basic colours, but even a laser display cannot reproduce all the colours the human eye can see, although it is quite close to doing that. However, in today’s monitors, both CRT and LCD (except for some models I’ll discuss below), the spectrum of each of the basic colours is far from monochromatic. In the terms of the CIE diagram it means that the vertexes of the triangle are shifted from the border of the diagram towards its centre.

Traditionally, LCD monitors were capable of giving approximate coverage of the sRGB reference colour space as shown in the diagram above. This is defined by the backlighting used in these displays – Cold-cathode fluorescent lamps (CCFL) that are employed which emit radiation in the ultraviolet range which is transformed into white colour with the phosphors on the lamp’s walls. These backlight lamps shine through the LCD panel, and through the RGB sub-pixels which act as filters for each of the colours. Each filter cuts a portion of spectrum, corresponding to its pass-band, out of the lamp’s light. This portion must be as narrow as possible to achieve the largest colour gamut.

Viewing angles are quoted in horizontal and vertical fields and often look like this in listed specifications: 170/160 (170° in horizontal viewing field, 160° in vertical). The angles are related to how the image looks as you move away from the central point of view, as it can become darker or lighter, and colours can become distorted as you move away from your central field of view. Because of the pixel orientation, the screen may not be viewable as clearly when looking at the screen from an angle, but viewing angles of TFT’s vary depending on the panel technology used.

TFT screens do not refresh in the same way as a CRT screen does, where the image is redrawn at a certain rate. As a TFT is a static image, and each pixel refreshes independently, setting the TFT at a common 60Hz native refresh rate does not cause the same problems as it would on a CRT. There is no cathode ray gun redrawing the image as a whole on a TFT. You will not get flicker, which is the main reason for having a high refresh rate on a CRT in the first place. Standard TFT monitors operate with a 60Hz recommended refresh rate, but can sometimes support up to 75Hz maximum (within the spec) or sometimes even further using ‘overclocking’ methods. The reason that 60Hz is recommended by all the manufacturers is that it is related to the vertical frequency that TFT panels run at. Some more detailed data sheets for the panels themselves clearly show that the operating vertical frequency is between about 56 and 64Hz, and that the panels ‘typically’ run at 60Hz (see the LG.Philips LM230W02 datasheet for instance – page 11). If you decide to run your refresh rate from your graphics card above the recommended 60Hz it will work fine, but the interface chip on the monitor will be in charge of scaling the frequency down to 60Hz anyway. Some screens will allow you to run at the maximum 75Hz as well for an additional boost in frame rates and some minor improvements in motion clarity. The support of this will really depend on the screen, your graphics card and the video connection being used. You may find the screen operates fine at the higher refresh rate setting but in reality the screen will often drop frames to meet the 60Hz recommended setting (or spec of the panel) anyway. Generally we would suggest sticking to 60Hz on standard TFT monitors.

You will see more mention of higher refresh rates from both LCD televisions and now desktop monitors. It’s important to understand the different technologies being used though and what constitutes a ‘real’ 120Hz and what is ‘interpolated’:

Interpolated 120Hz+– These technologies are the ones commonly used in LCD TV’s where TV signal input is limited to 50 / 60 Hz anyway (depending on PAL vs NTSC). To help overcome the issues relating to motion blur on such sets, manufacturers began to introduce a technology to artificially boost the frame rate of the screen. This is done by an internal processing within the hardware which adds an intermediate and interpolated (guessed / calculated) frame between each real frame, boosting from 50 / 60fps to 100 / 120 fps. This technology can offer a noticeable improvement in practice when it is controlled very well. Some sets even have 240 and 480Hz technologies which operate in the same way, but with further interpolation and inserted frames. See here for further information.

Manufacturer specifications will usually list power consumption levels for the monitor which tell you the typical power usage you can expect from their model. This can help give you an idea of running costs, carbon footprint and electricity demands which are particularly important when you’re talking about multiple monitors or a large office environment. Power consumption of an LCD monitor is typically impacted by 3 areas:

This relates to the connection type from the TFT to your PC or other external device. Older screens nearly all came with an analogue connection, commonly referred to as D-sub or VGA. This allows a connection from the VGA port on your graphics card, where the signal being produced from the graphics card is converted from a pure digital to an analogue signal. There are a number of algorithms implemented in TFT’s which have varying effectiveness in improving the image quality over a VGA connection. Some TFT’s with then offer a DVI input as well to allow you to make use of the DVI output from your graphics card which you might have. This will allow a pure digital connection which can sometimes offer an improved image quality. It is possible to get DVI – VGA converters. These will not offer any improvements over a standard analogue connection, as you are still going through a conversion from digital to analogue somewhere along the line. Dual-Link DVI is also sometimes used which is a single DVI connection but with more pins, allowing for higher resolution/refresh rate support than a single-link DVI.

The graphics display resolution is the width and height dimension of an electronic visual display device, measured in pixels. This information is used for electronic devices such as a computer monitor. Certain combinations of width and height are standardized (e.g. by VESA) and typically given a name and an initialism that is descriptive of its dimensions. A graphics display resolution can be used in tandem with the size of the graphics display to calculate pixel density. An increase in the pixel density often correlates with a decrease in the size of individual pixels on a display.

The favored aspect ratio of mass-market display industry products has changed gradually from 4:3, then to 16:10, then to 16:9, and is now changing to 18:9 for smartphones.cathode ray tube (CRT). The 16:10 aspect ratio had its largest use in the 1995–2010 period, and the 16:9 aspect ratio tends to reflect post-2010 mass-market computer monitor, laptop, and entertainment products displays. On CRTs, there was often a difference between the aspect ratio of the computer resolution and the aspect ratio of the display causing non-square pixels (e.g. 320 × 200 or 1280 × 1024 on a 4:3 display).

The 4:3 aspect ratio was common in older television cathode ray tube (CRT) displays, which were not easily adaptable to a wider aspect ratio. When good quality alternate technologies (i.e., liquid crystal displays (LCDs) and plasma displays) became more available and less costly, around the year 2000, the common computer displays and entertainment products moved to a wider aspect ratio, first to the 16:10 ratio. The 16:10 ratio allowed some compromise between showing older 4:3 aspect ratio broadcast TV shows, but also allowing better viewing of widescreen movies. However, around the year 2005, home entertainment displays (i.e., TV sets) gradually moved from 16:10 to the 16:9 aspect ratio, for further improvement of viewing widescreen movies. By about 2007, virtually all mass-market entertainment displays were 16:9. In 2011, 1920 × 1080 (Full HD, the native resolution of Blu-ray) was the favored resolution in the most heavily marketed entertainment market displays. The next standard, 3840 × 2160 (4K UHD), was first sold in 2013.

Also in 2013, displays with 2560 × 1080 (aspect ratio 64:27 or 2.370, however commonly referred to as "21:9" for easy comparison with 16:9) appeared, which closely approximate the common CinemaScope movie standard aspect ratio of 2.35–2.40. In 2014, "21:9" screens with pixel dimensions of 3440 × 1440 (actual aspect ratio 43:18 or 2.38) became available as well.

nHD (ninth HD) is a display resolution of 640 × 360 pixels, which is exactly one-ninth of a Full HD (1080p) frame and one-quarter of a HD (720p) frame. Pixel doubling (vertically and horizontally) nHD frames will form one 720p frame and pixel tripling nHD frames will form one 1080p frame.

One drawback of this resolution regarding encoding is that the number of lines is not an even multiple of 16, which is a common macroblock size for video codecs. Video frames encoded with 16×16 pixel macroblocks would be padded to 640 × 368 and the added pixels would be cropped away at playback. H.264 codecs have this padding and cropping ability built-in as standard. The same is true for qHD and 1080p but the relative amount of padding is more for lower resolutions such as nHD.

To avoid storing the eight lines of padded pixels, some people prefer to encode video at 624 × 352, which only has one stored padded line. When such video streams are either encoded from HD frames or played back on HD displays in full-screen mode (either 720p or 1080p) they are scaled by non-integer scale factors. True nHD frames on the other hand has integer scale factors, for example Nokia 808 PureView with nHD display.

The HD resolution of 1280 × 720 pixels stems from high-definition television (HDTV), where it originally used 50 or 60 frames per second. With its 16:9 aspect ratio, it is exactly 2 times the width and 11/2 times the height of 4:3 VGA, which shares its aspect ratio and 480 line count with NTSC. HD, therefore, has exactly 3 times as many pixels as VGA, i.e. almost 1 megapixel.

In the mid-2000s, when the digital HD technology and standard debuted on the market, this type of resolution was often referred to by the branded name HDr for short, which had specified it as a minimum resolution for devices to qualify for the certification. However, few screens have been built that use this resolution natively. Most employ 16:9 panels with 768 lines instead (WXGA), which resulted in odd numbers of pixels per line, i.e. 13651/3 are rounded to 1360, 1364, 1366 or even 1376, the next multiple of 16.

FHD (Full HD) is the resolution used by the 1080p and 1080i HDTV video formats. It has a 16:9 aspect ratio and 2,073,600 total pixels, i.e. very close to 2 megapixels, and is exactly 50% larger than 720p HD (1280 × 720) in each dimension for a total of 2.25 times as many pixels. When using interlacing, the uncompressed bandwidth requirements are similar to those of 720p at the same field rate (a 12.5% increase, as one field of 1080i video is 1,036,800 pixels, and one frame of 720p video is 921,600 pixels). Although the number of pixels is the same for 1080p and 1080i, the effective resolution is somewhat lower for the interlaced format, as it is necessary to use some vertical low-pass filtering to reduce temporal artifacts such as interline twitter.

DCI 2K is a standardized format established by the Digital Cinema Initiatives consortium in 2005 for 2K video projection. This format has a resolution of 2048 × 1080 (2.2 megapixels) with an aspect ratio of 256:135 (1.8962:1).

QHD (Quad HD), WQHD (Wide Quad HD),1440p,2560 × 1440 pixels in a 16:9 aspect ratio. The name QHD reflects the fact that it has four times as many pixels as HD (720p). It is also commonly called WQHD, to emphasize it being a wide resolution, although that is technically unnecessary, since the HD resolutions are all wide. One advantage of using "WQHD" is avoiding confusion with qHD with a small q (960 × 540).

This resolution has a 16:9 aspect ratio, and is exactly four times as many pixels as the 1600 × 900 HD+ resolution. It has been referred to as WQXGA+,QHDQHD+

This resolution, sometimes referred to as 4K UHD or 4K×2K, has a 16:9 aspect ratio and 8,294,400 pixels. It is double the size of Full HD (1920 × 1080) in both dimensions for a total of four times as many pixels, and triple the size of HD (1280 × 720) in both dimensions for a total of nine times as many pixels. It is the lowest common multiple of the HDTV resolutions.

The first commercial displays capable of this resolution include an 82-inch LCD TV revealed by Samsung in early 2008,PPI 4K IPS monitor for medical purposes launched by Innolux in November 2010.Toshiba announced the REGZA 55x3,

4096 × 2160, referred to as DCI 4K, Cinema 4K4K×2K, is the resolution used by the 4K container format defined by the Digital Cinema Initiatives Digital Cinema System Specification, a prominent standard in the cinema industry. This resolution has an aspect ratio of 256:135 (1.8962:1), and 8,847,360 total pixels.

This resolution is equivalent to 4K UHD (3840 × 2160) extended in width by 33%, giving it a 64:27 aspect ratio (2.370 or 21.3:9, commonly marketed as simply "21:9") and 11,059,200 total pixels. It is exactly double the size of 2560 × 1080 in both dimensions, for a total of four times as many pixels. The first displays to support this resolution were 105-inch televisions, the LG 105UC9 and the Samsung UN105S9W.5120 × 2160 monitor, the 34WK95U,5K2K WUHD.

This resolution, commonly referred to as 5K or 5K × 3K, has a 16:9 aspect ratio and 14,745,600 pixels. Although it is not established by any of the UHDTV standards, some manufacturers such as Dell have referred to it as UHD+.QHD (2560 × 1440) in both dimensions for a total of four times as many pixels, and is 33% larger than 4K UHD (3840 × 2160) in both dimensions for a total of 1.77 times as many pixels. The line count of 2880 is also the least common multiple of 480 and 576, the scanline count of NTSC and PAL, respectively. Such a resolution can vertically scale SD content to fit by natural numbers (6 for NTSC and 5 for PAL). Horizontal scaling of SD is always fractional (non-anamorphic: 5.33...5.47, anamorphic: 7.11...7.29).

Other resolution with the same 5120-pixel width, which is the lowest common multiple of popular 1024 and 1280, but a different aspect ratio have also been called "5K" and some nominal 5K resolutions are just 4800 pixels wide, which is the lowest common multiple of 960 and 800.

This resolution, sometimes referred to as 8K UHD, has a 16:9 aspect ratio and 33,177,600 pixels. It is exactly double the size of 4K UHD (3840 × 2160) in each dimension for a total of four times as many pixels, and Quadruple the size of Full HD (1920 × 1080) in each dimension for a total of sixteen times as many pixels. 7680 × 4320 was chosen as the resolution of the UHDTV2 format defined in SMPTE ST 2036-1,8K UHDTV system defined in ITU-R BT.2020UHD-2 broadcast standard from DVB.

Quarter-QVGA (QQVGA or qqVGA) denotes a resolution of 160 × 120 or 120 × 160 pixels, usually used in displays of handheld devices. The term Quarter-QVGA signifies a resolution of one fourth the number of pixels in a QVGA display (half the number of vertical and half the number of horizontal pixels) which itself has one fourth the number of pixels in a VGA display.

Half-QVGA denotes a display screen resolution of 240 × 160 or 160 × 240 pixels, as seen on the Game Boy Advance. This resolution is half of QVGA, which is itself a quarter of VGA, which is 640 × 480 pixels.

The name comes from having a quarter of the 640 × 480 maximum resolution of the original IBM Video Graphics Array display technology, which became a de facto industry standard in the late 1980s. QVGA is not a standard mode offered by the VGA BIOS, even though VGA and compatible chipsets support a QVGA-sized Mode X. The term refers only to the display"s resolution and thus the abbreviated term QVGA or Quarter VGA is more appropriate to use.

QVGA resolution is also used in digital video recording equipment as a low-resolution mode requiring less data storage capacity than higher resolutions, typically in still digital cameras with video recording capability, and some mobile phones. Each frame is an image of 320 × 240 pixels. QVGA video is typically recorded at 15 or 30 frames per second. QVGA mode describes the size of an image in pixels, commonly called the resolution; numerous video file formats support this resolution.

Wide QVGA or WQVGA is any display resolution having the same height in pixels as QVGA, but wider. This definition is consistent with other "wide" versions of computer displays.

Since QVGA is 320 pixels wide and 240 pixels high (aspect ratio of 4:3), the resolution of a WQVGA screen might be 360 × 240 (3:2 aspect ratio), 384 × 240 (16:10 aspect ratio), 400 × 240 (5:3 – such as the Nintendo 3DS screen or the maximum resolution in YouTube at 240p), 428 × 240 (≈16:9 ratio) or 432 × 240 (18:10 aspect ratio). As with WVGA, exact ratios of n:9 are difficult because of the way VGA controllers internally deal with pixels. For instance, when using graphical combinatorial operations on pixels, VGA controllers will use 1 bit per pixel. Since bits cannot be accessed individually but by chunks of 16 or an even higher power of 2, this limits the horizontal resolution to a 16-pixel granularity, i.e., the horizontal resolution must be divisible by 16. In the case of the 16:9 ratio, with 240 pixels high, the horizontal resolution should be 240 / 9 × 16 = 426.6, the closest multiple of 16 is 432.

WQVGA has also been used to describe displays that are not 240 pixels high, for example, Sixteenth HD1080 displays which are 480 pixels wide and 270 or 272 pixels high. This may be due to WQVGA having the nearest screen height.

WQVGA resolutions were commonly used in touchscreen mobile phones, such as 400 × 240, 432 × 240, and 480 × 240. For example, the Hyundai MB 490i, Sony Ericsson Aino and the Samsung Instinct have WQVGA screen resolutions – 240 × 432. Other devices such as the Apple iPod Nano also use a WQVGA screen, 240 × 376 pixels.

HVGA (Half-size VGA) screens have 480 × 320 pixels (3:2 aspect ratio), 480 × 360 pixels (4:3 aspect ratio), 480 × 272 (≈16:9 aspect ratio), or 640 × 240 pixels (8:3 aspect ratio). The former is used by a variety of PDA devices, starting with the Sony CLIÉ PEG-NR70 in 2002, and standalone PDAs by Palm. The latter was used by a variety of handheld PC devices. VGA resolution is 640 × 480.

Wide VGA or WVGA, sometimes just WGA is any display resolution with the same 480-pixel height as VGA but wider, such as 720 × 480 (3:2 aspect ratio), 800 × 480 (5:3), 848 × 480, 852 × 480, 853 × 480, or 854 × 480 (≈16:9).

It is a common resolution among LCD projectors and later portable and hand-held internet-enabled devices (such as MID and Netbooks) as it is capable of rendering websites designed for an 800 wide window in full page-width. Examples of hand-held internet devices, without phone capability, with this resolution include: Spice stellar nhance mi-435, ASUS E

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey