lifetime of lcd displays quotation

the contrast settings remains after being set, i.e., depends on calculator main hardware. It uses a four-bit range parameter (0 to 15), usually in the X-register. If you have HEPAX, try HEPAX function 005. Default contrast is 5 (0101) instead of expected 7 (0111)... Go figure!

Much has been made of the longevity of LCD displays, at least compared to plasma monitors. The conventional wisdom is that LCD televisions last longer than their plasma TV counterparts, which is true. The problem is, a lot of people extrapolate from this that either (a) LCD displays last forever or (b) LCD monitors suffer no picture "wear" over time. Neither of these suppositions is correct.

Flat-panel LCD screen displays have a lifespan approaching 60,000 hours. The lifespan of an LCD display is generally longer than that of similar-sized plasma displays. Some manufacturers even claim that their LCDs can last upwards of 80,000 hours when used continuously under controlled conditions (e.g., in a room with "standard" lighting conditions and 77° temperatures throughout). Just how realistic such claims are is debatable. After all, whose living room has no windows and remains at a perfectly comfortable 77 degrees year-round?

In any case, the pictures on LCD displays will show some "wear" because they are generated by powerful lamps, which, like any lighting appliance, will dim over time and with use. The picture you see will dim ever so slightly as the lamp itself dims.

Therefore, the most important thing to consider when it comes to the lifespan of your LCD TV is the actual lifespan of the light source in your LCD. LCD TVs last as long as their lightsources do. So, the lightsource in your LCD monitor is the critical component of your LCD display unit.

The quality of your lightsource is particularly important for maintaining a proper white balance on your TV. As these florescent bulbs age, colors can become unbalanced, which could result in too much red, for example, in your picture. So, it pays to buy name-brand displays. You will definitely pay more for better LCD display brands like Sharp, Toshiba, JVC, or Sony than you will for cheap Chinese or Korean variety knock-offs, but you"ll get a backlighting bulb of higher quality and, in the end, a TV whose colors will stay truer longer.

To ensure the integrity of your lightsource for the duration of your LCD display"s lifespan, you will definitely want to adjust the CONTRAST setting of your LCD TV. Too high of a CONTRAST level will prematurely age your lightsource because it will have to work harder to maintain such light intensities. Your best bet is to keep your CONTRAST set appropriately for the conditions under which your view your LCD display. Higher light levels require slightly higher CONTRAST levels, while lower ambient light levels demand less CONTRAST.

You will also want to pay attention to the warranty for this particular feature, since it can be shorter than for the display as a whole. This means you might have to buy a whole new LCD monitor because the coverage on its backlight has expired. Moreover, some bulbs can be replaced, while others are built in to the unit itself. You should definitely do some research on the backlighting system, how it"s configured, and how it"s warranted.

Note: Sharp is currently the only manufacturer that makes LCD displays whose lamps can be changed out. This is definitely something to consider, given that LCD monitors dim as their lightsources do, so being able to replace its lamp will restore your picture to "like new" levels.

Responsible for performing installations and repairs (motors, starters, fuses, electrical power to machine etc.) for industrial equipment and machines in order to support the achievement of Nelson-Miller’s business goals and objectives:

• Provide electrical emergency/unscheduled diagnostics, repairs of production equipment during production and performs scheduled electrical maintenance repairs of production equipment during machine service.

Perhaps you’ve wondered how long a digital display lasts. It’s a great question. One quick search on Google will tell you that an LCD panel has a lifespan of about 60,000 hours, which is equivalent to almost seven years.

Of course, LCDs aren’t the only kind of displays. You also have LED, OLED, QLED, ELD, PDP, and MicroLED, plus many other variations. Obviously, that 7-year estimation will not apply across the board. For the sake of ease, let’s just focus on some of the common types of displays that most of us are familiar with.

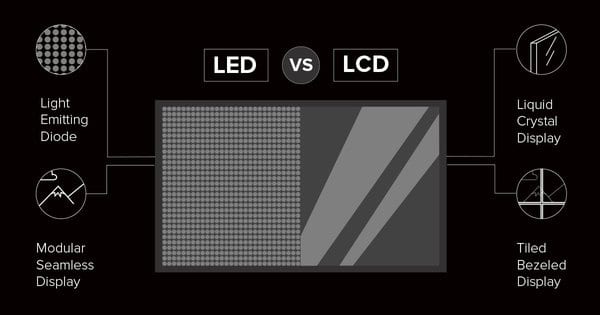

Here’s some LCD alphabet soup: There are LED LCD displays, CFFL LCD displays, LED displays, and more. With all these acronyms, it can get a bit confusing. What"s important to note is whether or not the display uses an LCD panel, and how the LCD panel is illuminated. You can read more about thedifferences between types of LCD and LED signage, but these are the most common types:

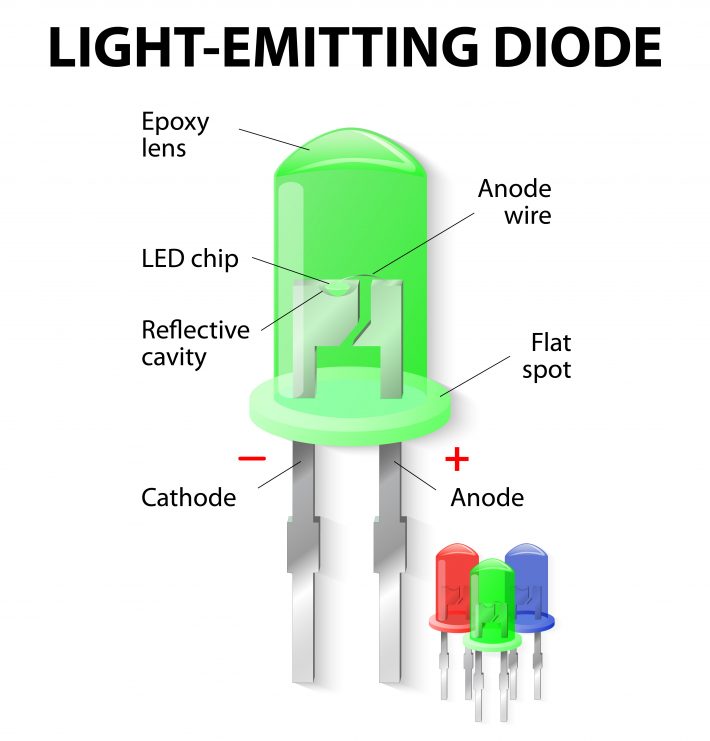

LCD displaysgenerate images and colors via a Liquid Crystal Display (LCD) panel, which is not self-emitting and requires an external light source to illuminate the image, typically an LED backlight. Their full name "LED-backlit LCD display" is commonly shortened to "LED displays", which is why they"re often confused with the true LED displays we"ve identified above.

Unfortunately, LED backlights used in LCD displays burn out over time. If used at high or maximum brightness, which is necessary for outdoor applications,an LED backlight will last between 40,000 to 60,000 hours. Or, about 4.5 to 7 years.

OLED stands for Organic Light Emitting Diode. OLED displays differ from common LCD displays in that their pixels are self-illuminating. In other words, there is no LED backlight required to illuminate the the display image; everything occurs within the OLED pixels themselves. According to onearticle from the US Department of Energy,OLED screens have a life expectancy of about 40,000 hours at 25% brightness, and 10,000 hours at full brightness. That equates to about 1 to 4.5 years, which is a much shorter (albeit, brilliant) lifetime than an LCD display.

Perhaps you noticed that the acronym QLED closely resembles the acronym OLED. This is not accidental. QLED is basically Samsung’s original design built to compete with OLED technology. However, the two are not the same. QLED stands for Quantum Light Emitting Diode. While QLED is similar to a regular LED design, it in fact differs by using nanoparticles called “Quantum dots” to achieve its unique brightness and color. Samsung approximates that the lifespan ofQLED panels are likely to last 7-10 years. After that, a user is likely to notice traces of degradation.

MicroLED is an emerging display technology, consisting of small LEDs in tiny arrays within each pixel. This technology goes beyond the offerings of the formerly frontrunning OLEDs, with much darker blacks and more radiant contrast levels. And, unlike OLEDs, MicroLEDs are not organic. They are not as subject to burn-in, and thus, have a longer lifespan than OLEDs. However, they are significantly more expensive - so much, in fact, that they aren’t considered a viable option for the majority of consumers.According to Samsung, the lifespan of its MicroLED panels should last about 100,000 hours, or, roughly 11 years.

PDP stands for Plasma Display Panel, and it refers to displays that use small cells full of plasma. The atoms within the plasma emit light upon being charged by electricity. While PDP is generally considered to offer better colors than LCDs, they consume a lot more power and usually cannot be battery-operated.The average lifespan of the newest generation of PDPs is approximated to be 100,000 hours, or 11 years of continual use.

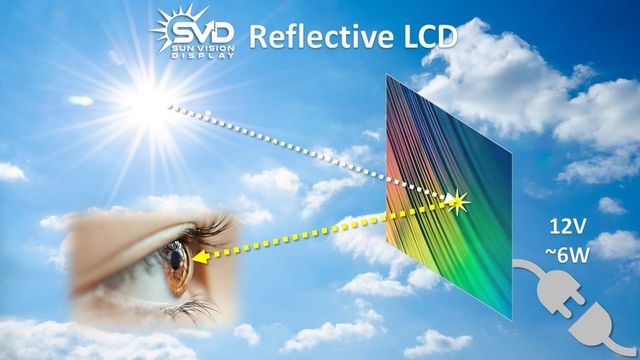

In some ways,reflective LCD panelsoperate similarly to other LCDs, only they have one key difference - they do not require a backlight. Instead, they rely on ambient light (or sunlight) in order to produce images. This opens the door to some groundbreaking possibilities. The first (and most appreciable) is low power consumption. Reflective displays use up to 95% less energy. Not bad - especially in a world that is continually looking for new ways to go green. Take into consideration the financial implications of this. Lower power means less money spent on operating costs.

Being that reflective displays do not require a backlight (a component that is particularly subject to degradation), and since they do not generate as much heat, it is safe to say that the lifespan of these displays should far exceed that of backlit LCD panels (which was 7 years at the high end). However, being that thisinnovative technologyis relatively new, its actual lifespan is therefore more difficult to estimate -- simply because it has yet to be reached.

There are also a few challenges that can affect reflective displays. For one, they rely on ambient light. On a nice sunny day, these displays perform beautifully and can be easily seen in even the brightest of conditions. This performance wanes as the available ambient light decreases. And, since they do not generate light of their own, they are not designed to be viewed under nighttime or extremely low light conditions (without additional lighting features). In short, their images are visible to the degree that ambient light is present. However, in light of this, side light (and front light) options are being explored.

One company at the front lines of this research isAzumo. Azumo has created a light guide that laminates to the front of a display. It requires 90% less energy than the backlight of a traditional LCD display. This greatly improves the problem of low light visibility otherwise encountered, and keeps reflective displays in the same low energy consumption ballpark. One issue, however, is that Azumo currently only offers its light guides for smaller-sized units. If you happen to want this feature applied to a display that is over 10” diagonally, then you’re still on the search for a solution.

Other “pioneer companies” are at the frontier of this research as well, and many are already innovating new solutions to increase the viability of reflective technology - both in their low light visibility and in the screen sizes they are available in. Due to the huge potential offered by reflective technology, it is fair to assume that we will see even greater enhancements to it in the very near future.

One other factor to consider regarding reflective technology is its cost. That reflective layer is more costly to manufacture than many of the backlights it replaces, creating a seemingly greater upfront cost for those who are interested in investing in energy-efficient signage. However, these initial price points are quickly justified as buyers will recognize the significantly lower operating costs and increased longevity (not even including replacement costs of other “expired” displays) that comes with their purchase of reflective display signage. If a backlit LCD panel only lasts 7 years, for example, you’ll have paid for that LCD twice in the period of ten years. A very valid question arises… is that “cheaper” backlight really cheaper? Probably not. It only feels that way at first.

Sun Vision Displayis working hard to create reflective display solutions for the digital signage world. We are currently offering them in 32" and 43" diagonal sizes, with a 55” size in development. These displays are built formany environments. We are thrilled to be bringing such innovative solutions to the market.

If you have any questions, or if you would like to talk to a representative about how our solutions might work for you, please don’t hesitate to contact us. Simply scroll down to the bottom of the page to our form, and we’ll get back to you in a timely manner. We look forward to the possibility ofworking with you!

500 hours? I"m surprised. I would have thought some of the prints would take 5-10 hours, which makes that 50-100 prints per panel. That seems low. Quoting from that page:

I"m skeptical it is really that low or if they are being overly conservative for liability purposes. I"m also curious about the failure mechanism. If it is pixels stuck on or off, that could be an issue. If it is hazing or decreased transmissiveness(word?) it might just lead to longer exposure times required.

The life span of traditional LCD screens is between 40,000 and 60,000 hours, and the more recent popular OLED screens have a life span of about 30,000 hours. If you look at the phone for an average of 3 hours a day, it can also last 10,000 days, or 27 years, which is far more than the average user’s replacement cycle.

OLED display technology, which uses a very thin coating of organic material and a glass substrate (or flexible organic substrate) that emits light when an electric current is passed through it.

Nowadays, OLED screen has become the standard for high-end smartphones, compared with the traditional LCD technology, it is not only thinner, lower energy consumption, high brightness, can display pure black, faster response time, but also can be made into a curved screen, giving people a different visual impact

Today’s major international manufacturers are scrambling to strengthen the research and development investment in OLED technology, making OLED technology in today’s TVs, computers (monitors), cell phones, tablets and other areas of spiritual applications more and more widespread.

Why under-screen fingerprint recognition can only be used in OLED screen? This is because it is relatively “soft”, OLED in the construction of only two layers of thin film and glass or plastic substrate, and through the OLED material self-lighting characteristics, can be without backlight module and color filter, also do not need the general LCD panel filling liquid crystal process, can achieve 0.5-1.8mm thickness. Nowadays, most of the under-screen fingerprint recognition is optical fingerprint program, so relatively in the use of optical fingerprint program, OLED screen will be more suitable.

Why can’t under-screen fingerprint recognition be used in LCD screen? This is because it is relatively “hard”, the working principle of LCD is mainly composed of two parallel glass plate, between the two layers of glass plate and then by the liquid crystal layer and polarizer, color filter layer and so on material composition. In simple terms, LCD is the need for backlight irradiation to display, so is the result of LCD screen than OLED screen thicker, light transmission is weaker, not conducive to the use of under-screen fingerprint identification.

Since OLED screen can use under-screen fingerprint recognition, why do not all cell phone manufacturers use OLED screen? This involves the advantages and disadvantages of LCD screens and OLED screens.

OLED screen has the advantage of being able to achieve the integration of on-screen fingerprints without opening holes, as well as a wide color gamut, but there are also certain defects, short life, easy to burn the screen (if the same screen bright screen for a long time, the screen will leave that long-term static picture traces), low pixel density, etc., and the overall technology is not mature enough, due to the low pixel density of OLED screen, it is difficult to have 2K, 4K screen.

LCD screen, although temporarily can not use under-screen fingerprint recognition, but, LCD screen is also the advantages of OLED can not be comparable, there is a natural DC dimming more eye protection, color is also natural, drawing people prefer LCD, screen life compared to OLED long, but also not easy to change color, also do not have to worry about using a long time after the problem of burning screen, which is also the reason why LCD loyal users like it.

In addition, LCD screen does not stimulate the human eye, will not cause eye fatigue, especially open eye protection mode filtering blue light, less damage to the eyes. oled screen will leave residual shadows, eye damage, even dimming can not be completely avoided.

Deciding when it’s time to replace your digital display can be tough. After all, you want to get as much use as possible out of your investment. But even the best displays don’t last forever. It’s important to consider upgrading your LED display to not only remain competitive and compliant, but also to avoid having to use more power to keep it running. With a newer setup, you can ensure lower energy costs and worry less about downtime.

You should also consider how long your manufacturer stated your board would last. Perhaps your specific board was quoted as a 10- to 12-year lifespan. If you’re approaching the end of that range, it may be time to look into an upgrade — while you still have the luxury of time. With age also comes warranty concerns. If your display has aged out of its warranty, any issues that arise can be costly to fix.

Even with the best maintenance, displays are subject to mechanical issues and failure. Older displays, especially those outdoors, receive a lot of environmental wear and tear over the years. Sunlight fades and degrades individual diodes, decreasing display brightness and picture consistency. With an inconsistent picture, your display is less valuable to both you and your advertisers. And as with any aging product, parts can fail. It happens, and without a warranty to replace or repair, those parts can be a big hit to your budget — if you can find obsolete parts at all.

Like it or not, cost is always a contributing factor, and evaluating the LED display board cost of your current board versus an upgrade is another effective way to weigh your options. Some considerations include:

With rapid advancements in display technology, an upgrade may be necessary to stay competitive or compliant. Samsung’s MagicINFO, an all-in-one digital signage platform, is also an option that can help you manage the software and the hardware of your LED displays and optimize their performance, all from one place.

Sometimes, technology evolves so much over time that businesses are forced to upgrade. Accelerated tech advancements and higher industry standards can take shape in a number of different ways, including:

Pixel pitch has continued to decrease and brightness standards are also changing. Not long ago, 5,000 nits marked ideal brightness. These days 7,500+ nits is the expectation. On top of pixel pitch and brightness, the industry has come to expect additional capabilities like better uptime, cloud-based management and HDR color.

The major rule of thumb: Your board should give you headroom, giving you the flexibility to grow with industry standards. If you’re already at max capacity, it may be time to upgrade.

Ready for an upgrade? Explore Samsung’s full line ofLED solutionsfor your business — and get yourfree, complete guideto configuring and tailoring real-time messaging using an integrated content management system.

Yep, rate and type of decay can vary throughout a lights life. EOL is generally specced as when it reaches 1/2 brightness and may become unsatisfactory to use before then.

If OLED were capable of being a lot brighter, the normal use wear rate would be much lower (reducing static image retention issues as well) and HDR would look a lot better.

If you"re looking for lifespan, CRTs are the way to go. The reason CRTs dim is that the phosphors in the tube slowly escape as they are bombarded by current. Yes, mikef, they dim. But very slowly. However, with a CRT, you"re looking at all kinds of other problems like heat and inconsistency. A flicker is also noticeable in low-end CRTs.

LCDs have a much shorter lifespan, for the same reason as everyone else has said -- The backlight grows dimmer. To answer your question, most modern LCD monitors will be at half brightness after about 60,000 hours, about 5 years for many computer users. But in the past 2 years, their performance has begun to blow away CRT monitors, which were traditionally much better in terms of quality. Also, LCDs are much easier to dispose of.

If you"re looking for lifespan, CRTs are the way to go. The reason CRTs dim is that the phosphors in the tube slowly escape as they are bombarded by current. Yes, mikef, they dim. But very slowly. However, with a CRT, you"re looking at all kinds of other problems like heat and inconsistency. A flicker is also noticeable in low-end CRTs.

LCDs have a much shorter lifespan, for the same reason as everyone else has said -- The backlight grows dimmer. To answer your question, most modern LCD monitors will be at half brightness after about 60,000 hours, about 5 years for many computer users. But in the past 2 years, their performance has begun to blow away CRT monitors, which were traditionally much better in terms of quality. Also, LCDs are much easier to dispose of.

Of course, everyone is aware of televisions and monitors, but what about the low-level radiation from LCD monitors? Are there reliable studies on this?

Oh boy, this will certainly NOT prolong the life span of the background lighting. Don"t do this as constantly switching the lamps on and off wears them out VERY quickly. This results in the lamps needing more and more time to reach full brightness when switching the display on. The effect can already be seen after less than one year!

Good advice, or do the following: whenever you leave your computer for more than five minutes, turn the display off manually (if you have an external one) and don"t use the timed switch-off function.

What happened to me constantly: whenever I came back to my desktop, the display would switch itself off JUST at the time I came back. Then waking the screen could destroy it very quickly...

What I"m curious about is where you got this idea that LCD monitors even would produce any appreciable amount of low-level radiation. I don"t mean any offense, and I could be wrong without doing any research on it, but it seems rather absurd to me.

I cannot think of any major components in an LCD TV/Monitor that would even produce such radiation. As far as I know, they hardly produce any radiation but that on the visible spectrum, which is obviously necessary.

TFT monitors do not emit radiation at all (compared to CRT monitors). The TCO standard was developed for CRT monitors first, then TCO-99 added TFT / LCD monitors as well.

Spatial uniformity of displayed luminance can vary widely between different makes and models of LCD, the major determinant of uniformity being the backlight scheme [34] (some older LCDs allowed VGA input and relied on built-in analog-to-digital conversion, also a potential source of noise). Two commonplace schemes are, first, direct backlighting, wherein a spatial array of light-emitting diodes (LEDs) and a diffuser screen sit behind the liquid crystal panel, and, second, edge illumination, wherein light emitted by a linear array of diodes at one of the display’s edges is spatially distributed via lightguide. We quantified the spatial uniformity of the CG247X by presenting low-, medium-, and high-luminance static test patches at nine display positions (Fig 2, inset) and using the LS-110 spot meter to measure the luminance of each patch. At each luminance tested, we calculated the grand average over all display positions, and divisively normalized measurements by that average. As illustrated in Fig 2, at medium- and high-luminance, the CG247X showed greater spatial uniformity than our consumer-grade LCD (Dell U2415b): for the CG247X, spatial variation was 5.1% at medium and 3.5% at high luminance, whereas for the U2415b, variation was 8.1% at medium and 8.5% at high luminance. The uniformity of the two displays was comparable at low luminance (CG247X, 27% versus U2415b, 17%). Prior to normalization, there were, as expected, marked differences between low-, medium-, and high-luminance measurements. For example, at display position 5 (Fig 2, inset) on the CG247X, low-luminance measurements ranged from 0.07 to 0.10 cd/m2, medium-luminance measurements ranged from 57.70 to 57.93 cd/m2, and high-luminance measurements ranged from 113.9 to 114.2 cd/m2 (Table 1). We also quantified spatial surround effects; using a tripod at 1 m, we measured displayed luminance at position 5 comparing large (1920-by-1200 pixels) and small (384-by-384 pixels) 100%-luminance patches. For CG247X, the mean of 10 large-patch measurements was 0.56 cd/m2 greater than that of 10 small-patch measurements (two-sample t-test, p < 0.01), i.e., an increase of 0.50%. For the U2415b, the increase was 0.71 cd/m2, i.e., 0.67% (two-sample t-test, p < 0.01).

In-plane switching (IPS) LCDs, like our CG247X and U2415b, enable larger viewing angles than older LCD technology (e.g., twisted-nematic displays) [23]. To do so, IPS displays interdigitate electrodes (see 23]. For the displays we tested, vendor-issued specifications state a viewing angle of 178 deg, however, in the absence of further details, that derived measure is difficult to assimilate. We measured displayed luminance as a function of viewing angle over a range of azimuth and elevation (±60 deg). We fit a circular von Mises function (Fig 3, the CG247X and U2415b performed comparably in this regard. For the CG247X, the FW90M was 28.6 deg (fitted parameters: α = 1.45, κ = 3.37) and 32.6 deg (α = 1.65, κ = 2.62) for azimuth and elevation, respectively. For the U2415b, the FW90M was 31.2 deg (α = 1.60, κ = 2.85) and 31.0 deg (α = 1.55, κ = 2.90) for azimuth and elevation, respectively. At high-luminance we made a reduced set of measurements, assuming rotational symmetry, varying azimuth or elevation from 0 to 60 deg. These additional measurements yielded similar FW90M estimates. This descriptive model can be used to select a viewing distance with tolerable attenuation due to viewing angle. For example, if the CG247X is viewed from 1 m, a stimulus presented at the top of the display’s vertical meridian (i.e., elevation = 9.2 deg) would, due to viewing angle, undergo luminance attenuation by a factor of 0.97.

A common misconception among vision researchers and clinicians is that LCDs do not flicker (i.e., that LCDs are temporally uniform). In fact, there are two major sources of flicker that can affect a LCD: first, backlight flicker which usually occurs at temporal frequencies (e.g., 1000 Hz) well beyond the critical flicker fusion frequency (e.g., Elze & Tanner [24], and Ghodrati, Morris, & Price [35]), and, second, the so-called frame response which occurs at the refresh rate of the display (here, 60 Hz) [23, 36]. Frame responses are largely attributable to an LCD’s inversion scheme: a feature of modern displays wherein the polarity of the video signal voltage applied to the liquid crystal material is inverted from one video frame to the next. This inversion minimises long-term degradation, or aging, of the display by minimizing the DC voltage across the liquid crystal elements. Frame inversion schemes typically have fine spatial structure, on the scale of individual pixels, making them mostly imperceptible (e.g., dot inversion schemes [36]). We quantified the temporal uniformity of the CG247X by presenting (nominally) static test patches at display position 5 (Fig 2, inset) and using the linearized photodiode device to measure displayed luminance over time. At each of 11 luminances (0, 10, 20 … 100%) we made 10 one-second recordings, averaging the Fourier amplitude spectra of those 10 recordings. Fig 4 shows the average spectrum at each luminance. The spectra of the CG247X revealed a frame response comprising a 60 Hz component as well as harmonic components at integer multiples of 60 Hz. The response at 60 Hz varied non-monotonically in amplitude with the luminance of the static test patch, peaking at a luminance of 50%. However, the CG247X appeared free of backlight modulations. This absence of backlight modulations freed us of the consequences of said modulations (often desynchronized with the frame refresh signal) on increment/decrement transitions between luminances (see Fig 5 in [24]). The spectra of our consumer-grade LCD also revealed a frame response, as well as 1.2 kHz flicker, likely associated with the back light. This latter temporal nonuniformity increased linearly with the luminance of the static test patch.

We presented nominally static test patches at display position 5 (Fig 2, inset), measuring luminance with a linearized photodiode device. At each luminance (0, 10, 20 … 100%) we made ten 1-second recordings, deriving the Fourier amplitude spectrum for each. Each spectrum illustrated is the average of 10 spectra. For each display, we normalized spectra such that 1000 corresponds to the DC component at 50% luminance; therefore, a value of 5.0 corresponds to approximately 0.15 cd/m2. The spectra of the CG247X (upper) revealed a frame response, comprising a 60 Hz component and harmonic components at integer multiples of 60 Hz. This frame response varied non-monotonically in amplitude with the luminance of the static test patch, peaking between 40 and 50% luminance. The spectra of the U2415b (lower) also revealed a frame response, as well as 1.2 kHz flicker, the amplitude of which increased linearly with the luminance of the static test patch (amplitudes above 5.0 are not shown, arrowheads). For the U2415b, mains noise (50 Hz) was apparent at high-luminance. lum., luminance.

For each display, we verified that the frame response was optical and not related to any radiated electromagnetic noise: We used the oscilloscope to visualize the Fourier amplitude spectrum online. We then interposed opaque cardboard between the photodiode and display which caused the disappearance of the frame response. For the U2415b, we similarly verified that the 1.2 kHz response was optical.

In general, LCD response times—the duration of the rise or fall of a step from one luminance level to another—vary as a function of both step source and destination luminance. This nonlinear behaviour is owing largely to mechanisms of response time compensation (RTC) (e.g., the work of McCartney [25]), a feature of many modern LCDs designed to enhance video. RTC mechanisms speed luminance transitions by transiently altering the voltage applied to the liquid crystal associated with individual pixels (e.g., Fig 1 in [27]; Fig 5 in [24]). We measured the CG247X’s response times by presenting luminance steps—both increments and decrements—to the linearized photodiode device. Step source and destination took values 0, 25, 50, 75, or 100%. As illustrated in Fig 5, response times varied as a function of both luminance step source and destination. For example, stepping from 0% luminance to 25% luminance took 24.5 ms, stepping from 75% to 100% took 12.9 ms, and stepping from 25% to 0% took 8.1 ms. All of these steps are the same height, but response times differ markedly. Overall, the response times of our consumer-grade LCD were less than the CG247X response times. However, as we will illustrate below, faster is not better; although RTC mechanisms reduced the response times of our consumer-grade LCD, they contaminated displayed luminance with overshoot and undershoot artifacts which are problematic for many applications in clinical and experimental vision research, including the presentation of mean-modulated flicker. RTC mechanisms lower “black-white-black” and “grey-to-grey” response times, which are used to promote displays to the gaming community and other consumer markets.

(A) CG247X response times. The leftmost gray box (labelled “0%”) encompasses four points showing mean response times for transitions from source luminance = 0% to destination luminances = 25, 50, 75, and 100% (x axis). These rise times (upward triangles) decreased with increasing destination luminance. The gray box labelled “25%” shows mean response times of transitions from source luminance = 25% to destination luminances = 0, 50, 75, and 100%. The fall time (downward triangle), from 25% to 0% luminance, was less than the rise times. Overall, response times varied as a function of both source and destination luminance, as is generally expected of LCDs. We made 10 measurements at each source/destination luminance pair; error bars, where not obscured by symbols, mark the full range (from minimum to maximum) of these 10 measurements. (B) U2415b response times. Graphical conventions are as in A. Overall, U2415b response times were less than CG247X response times.

At the outset of this study, we made preliminary measurements similar to those illustrated in Fig 5. We noticed that rise and fall times straddling 50% luminance were approximately equal (e.g., rise time from 25% to 75% = 16.3 ms; fall time from 75% to 25% = 17.1 ms) which led us to wonder whether the CG247X could be used to display achromatic, mean-modulated flicker without the introduction of unworkable artifacts. To better determine the CG247X’s potential suitability for presenting mean-modulated flicker, and its susceptibility, or otherwise, to overshoot and undershoot artifacts typical of LCDs implementing RTC mechanisms, we presented mean-modulated flicker on both the CG247X and our consumer-grade display, using the linearized photodiode device to measure luminance over time. We used a flicker period of 20 frames (333.3 ms), and contrast ranging from 20 to 100%. As illustrated in Fig 6, the consumer-grade display’s luminance traces revealed overshoot and undershoot artifacts symptomatic of RTC. The CG247X’s luminance traces, however, appeared free of RTC artifacts. We used these traces to estimate response times specific to mean-modulated flicker, illustrated in Fig 7. Overall, CG247X rise and fall times were greater than those of our consumer-grade LCD. However, with the exception of 100% contrast, CG247X rise and fall times were approximately equal, indicating its potential suitability for presenting mean-modulated flicker.

Flicker period = 20 frames (333.3 ms), and contrast = 20 to 100% in increments of 20 as marked. At 40% contrast, the arrowheads show examples of luminance step source and destination as used in the computation of response times (Fig 7). For each display, we normalized traces to the luminance step destination at 100% contrast. For the U2415b, over- and undershoot are readily apparent at low and moderate contrast. The CG247X, however, shows exponential rise and fall, regardless of contrast.

Overall, CG247X (A) rise (upward triangles) and fall (downward triangles) times were greater than U2415b (B) rise and fall times. With the exception of 100% contrast, CG247X rise and fall times were approximately equal, indicating its potential suitability for presenting mean-modulated flicker. Each symbol represents the mean of 10 measurements. Error bars, where not obscured by symbols, mark the full range (minimum to maximum) of the 10 measurements.

To further determine whether the CG247X could be used to display achromatic, mean-modulated flicker without the introduction of unworkable artifacts, we presented flicker at frequencies ranging from 0.94 to 30 Hz and contrasts ranging from 20 to 100%. We used recorded traces (similar to those in Fig 6) to derive cycle-averaged luminance. In Fig 8, we illustrate how cycle-averaged luminance was approximately constant for all flicker frequencies, and for contrasts up to 80%. At 100% contrast, cycle-averaged luminance decreased with flicker frequency, indicating that, at full contrast, the monitor is not suitable for presenting mean-modulated flicker. Cycle-averaged luminance recorded from our consumer-grade LCD (Dell U2415b) varied as a function of flicker frequency at all contrasts tested; this variation is problematic for presenting achromatic, mean-modulated flicker. We also used CG247X traces to derive cycle-averaged r.m.s. luminance. In Fig 8, we illustrate how cycle-averaged r.m.s. luminance decreased with flicker frequency, indicative of loss of contrast. The consumer-grade LCD was affected by both changes in cycle-averaged luminance and loss of contrast.

We presented mean-modulated flicker at a range of flicker frequencies (0.94 to 30 Hz) and contrasts (20 to 100%). We used waveforms (e.g., Fig 6) recorded from the CG247X (A) to derive cycle-averaged luminance; we divisively normalized that derived measure using the cycle-averaged luminance of a “reference” waveform, that is, the response to contrast = 20% and flicker frequency = 0.94 Hz. This relatively low-contrast, low-frequency waveform was chosen as reference because it should be easily realized by both displays. For clarity, cycle-averaged responses for contrast = 40, 60, 80, and 100% are offset by -0.1, -0.2, -0.3, and -0.4 log units, respectively (arrowheads). As shown, cycle-averaged luminance was approximately constant for contrast = 20 to 80% at all flicker frequencies tested (0.94 to 30 Hz). At contrast = 100%, cycle-averaged luminance decreased with flicker frequency. Cycle-averaged luminance recorded from the consumer-grade U2415b (B) increased with flicker frequency at all contrasts tested. Graphical conventions are as in A. We used waveforms recorded from the CG247X (C) to derive cycle-averaged r.m.s. luminance; we divisively normalized that derived measure using cycle-averaged r.m.s. luminance of the reference waveform (20%, 0.94 Hz). As shown, at all contrasts tested (20 to 100%), cycle-averaged r.m.s. luminance decreased with flicker frequency, indicative of a loss of effective contrast. Cycle-averaged r.m.s. luminance recorded from the U2415b (D) revealed both increases and decreases to effective contrast with flicker frequency. Each symbol is the average of 10 measurements. (None of the data in panels C and D is offset.) We modeled cycle-average luminance and r.m.s. luminance on the CG247X as a causal exponential decay (Methods). This model comprised one free parameter, τ. For the illustrated fit (blue), τ = 6.6 ms. The red symbols in panel C (slightly offset rightward for clarity) show the result of a validation experiment (see

Taken together, Fig 8, and the traces used to derive the measures plotted there, indicated a simple relationship between nominal and displayed luminance on the CG247X, namely, that the latter was, simply, a low-pass-filtered version of the former. To test this hypothesis, we modeled the function transferring nominal luminance to displayed luminance as a causal, exponential decay (Methods). We optimized the single free parameter in this model, the time constant of the exponential decay (τ), by minimizing the sum of the squared error between the model-derived cycle-averaged mean luminance and cycle-averaged r.m.s. luminance, and those derived from the photodiode traces. For the CG247X, the fit is illustrated in Fig 8 (blue). There, the fitted parameter, τ, was 6.6 ms. To assess the fit to cycle-averaged luminance, we computed the root-mean-square error (RMSE) separately at each flicker contrast. For the CG247X, the RMSE was negligibly small for contrasts from 20 to 80% (ranging from 6.0e-4 to 6.3e-3 normalized units). At 100% contrast, RMSE was highest at 0.093. This simple model was a poor fit to the U2415b, not illustrated in Fig 8. For the U2415b, RMSEs were high, ranging from 0.04 at 20% contrast to 0.15 at 60% contrast. To assess the fit to cycle-averaged r.m.s. luminance, we calculated the square of Pearson’s correlation coefficient, R2, separately at each flicker contrast. For the CG247X, R2 was high, ranging from 0.9965 to 0.9999. As expected, the same calculation for the U2415b was consistent with a poor fit; at its worst, R2 = 0.03.

To quantify the nonlinearities associated with high-contrast, mean-modulated flicker, and to quantify temporal dependence between frames, we used a paired-pulse paradigm [37, 38]. We presented paired biphasic luminance pulses at position 5 (Fig 2, inset), systematically varying the inter-pulse interval, T (Methods). We used the measured responses to individual pulses to predict paired-pulse responses, and to model the display’s nonlinearities we subtracted each paired-pulse response from its prediction. Fig 9 shows the nonlinear behaviour of the CG247X and, for comparison, that of our consumer-grade LCD. In our CG247X, a nonlinear mechanism appeared to speed the transition between white and black (100% and 0% luminance, respectively; leftmost upper panel in Fig 9B). When paired pulses were separated by 16.67 ms or more (the three rightmost upper panels in Fig 9B where predicted and displayed luminance are approximately equal), the CG247X behaved linearly, that is, we saw no evidence of temporal dependence between frames. In our consumer-grade LCD, a nonlinear mechanism appeared to attenuate the transition to white (100% luminance; leftmost lower panel in Fig 9B). This attenuation reconciles with Fig 6 (lower), which shows marked overshoot at moderate contrast (e.g., 60% contrast, middlemost panel of Fig 6), but a near absence of overshoot at high-contrast (rightmost panel of Fig 6). Compared to the CG247X, the U2415b’s nonlinearities were large in magnitude and long-lasting. Paired pulses separated by as much as 33.33 ms (the third lower panel in Fig 9B, where predicted and displayed luminance are unequal) evoked nonlinear behaviour in the U2415b, that is, we saw clear evidence of temporal dependence between frames.

(A) Illustration of the paired-pulse paradigm. We presented a single biphasic luminance pulse (e.g., left panel), parametrically varying its latency relative to a trigger (cf. left and middle panels). We then presented a pair of biphasic luminance pulses (right panel), parametrically varying the offset between pulses comprising the pair, T = 0, 1, 2, and 3 times the frame period (frame period = 16.67 ms). Single-pulse responses can be used to predict the paired-pulse response; differences between this prediction and the displayed luminance model the display’s nonlinearities. (B) Nonlinear behaviour of the CG247X (upper). The four panels show responses to paired pulses with various offsets, T; we normalized responses (0, 0.5 and 1 corresponded to 0, 50 and 100% luminance, respectively) and then subtracted the baseline. For each offset, the predicted displayed luminance derived from single-pulse responses is shown in blue, and the measured displayed luminance in response to paired pulses is shown in black. The measured responses are an average of 16 recordings. The difference, that is, the nonlinearity, is shown in red. For the CG247X, superposition (T = 0 ms) of pulses evoked a nonlinearity which accelerated the transition from 100% luminance to 0% luminance. There was negligible nonlinearity of displayed lumiance for T > = 16.67 ms. Compared to the CG247X’s nonlinearity, the U2415b’s nonlinearity (lower panels) was large in magnitude and long-lasting, affecting subsequent frames (to T = 33.33 ms). Graphical conventions are as in B.

LED stands for Light Emitting Diode. SMD refers to Surface Mounted Diode, a technology that utilizes a process of mounting each LED chip (pixel) directly to a printed circuit board (PCB). Mounting the diodes in this fashion allows displays to be thinner and sleeker than older LED technology. SMD also allows for finer pixel pitch. Simply put, pixel pitch refers to the distance between the diodes and is responsible for resolution. Fine pixel pitch translates into high resolution. Fine pixel pitch is what makes HD and UHD LED possible.

LCD panels are made of a layer of liquid crystal between two pieces of polarized glass. Liquid crystal can not emit light. Backlights are therefore used to illuminate the display. LCD panels are sleek in design, but typically limited to specific sets of dimensions.

LEDs are their own light source. This means that LED video walls are glare free and not subject to many of the problems ambient lighting creates for other video display types.

LED technology is modular in nature. This means that LED panels fit together seamlessly and can be used to make displays to fit any space. Custom cabinets can even be built to accommodate unusual shapes or dimensions.

LCD video walls on the other hand take on a tiled approach. This means that screens are jutted against one another. This approach creates bezels or seams and the final dimensions of the wall is directly dependent on the dimensions of the individual screens.

LED is a versatile display option. Thanks to various IP options, LED video walls can be displayed indoors or outdoors. LED video walls can be built with a variety of internal mechanisms as well. Quick refresh rates and dual power backup can ensure that LED video walls look great on camera. Various pixel pitches can ensure the proper resolution for the right context.

LCD is a more straightforward product and consumers are generally more familiar with LCD. LCD is used for cell phones, computer screens, and most TVs, but is it the best choice for video walls? Ultimately that choice is up to the consumer. LCD is cheaper, but generally less customizable. LCD does not work well for outdoor uses and is generally very limited in terms of size and shape.

LED technology has improved drastically in recent years improving quality while driving costs down. LED is a bigger investment up front but generally has a lifespan of about 100,000 hours.

Just like anything else, the best video wall product is largely dependant on context. If you like LED technology but are unsure of the process associated in obtaining a LED video wall read: How to Purchase a LED Video Wall Display.

This paper reports the reliability of twisted nematic liquid-crystal display for basic applications such as watches and calculators. We have studied significant stress factors such as voltage, temperature and humidity, and their corresponding failure modes. The main failure mode is LCD misalignment; many different modes appear corresponding to different stress conditions as well as material and process for the LCD. We have analyzed the accelerated test results by Weibull distribution, elucidated accelerating factors, and estimated life time. The life is inversely proportional to 1.78-2.45 power of applied voltage, depending upon misalignment modes. The distribution of life is well expressed by Weibull distribution with shape parameter between 2.5-3.0, and proportional to the square of coefficient of variation of life. We conclude that the acceleration factors could be determined and 99.9% of tested displays will live more than 10 years. The knowledge on reliability of LCD can be now applied to new fields of LCD, such as industrial use, home appliance, and automotive instruments.

If you are new to the world of digital projectors, you won"t have to shop around long before discovering that the terms LCD and DLP refer to two different kinds of projectors. They are in fact two different kinds of microdisplay imaging technology. You might not even know what LCD and DLP are before asking the obvious question "which one is better?"

The answer is simple--neither one is better than the other. They both have advantages over the other, and they both have limitations. Both technologies are much better than they used to be. The purpose of this article is to discuss how they differ today, so you can determine whether the imaging technology itself is a relevant factor in your choice of a projector.

It is important to note there is a third significant light engine technology called LCoS (liquid crystal on silicon). It is developed and marketed by several vendors, most notably Canon, JVC, and Sony. Many excellent projectors have been made with LCoS technology, including several outstanding home theater projectors that can, in the opinion of many observers, surpass the value proposition of both LCD and DLP offerings. The discussion of LCoS technology is beyond the scope of this article, and will be addressed separately in an upcoming article.

You may have already seen the term 3LCD on websites and in projector literature and press releases. Several makers of LCD projectors have adopted 3LCD as a marketing brand name. It is intended to distinguish the specific implementation of LCD technology found in digital projectors from the more common direct view LCD displays found in a wide variety of consumer products. In LCD projectors there are always three LCD panels, and they are always light transmissive devices rather than reflective or direct view displays. Within the projector industry, there is no technical difference between 3LCD and LCD, and the terms can be used interchangeably.

Well, the answer to this question depends on your definition of the word "lead." As of this writing, DLP technology has a significant lead in terms of the number of models currently in production. As of this date, July 28, 2009, our database lists 704 different DLP-based models in production, as compared to 430 LCD models. Thus, DLP holds a commanding lead in the number and variety of models being produced.

However, this is not the whole story. Many of the best selling projectors these days are LCD models. As an example, at the moment, six of the Top 10 Most Popular 1080p home theater projectors on this site are LCD"s, two are DLP and two are LCoS. In fact, despite the clear advantage DLP has in the number of models in production, Pacific Media Associates reports that LCD projectors held a 51% market share by unit volume in 2008. Clearly both technologies have a huge market presence, and neither one is about to emerge as the dominant player.

LCD (liquid crystal display) projectors contain three separate LCD glass panels, one each for the red, green, and blue components of the video signal. Each LCD panel contains thousands (or millions) of liquid crystals that can be aligned in either open, closed, or partially closed positions to allow light to pass through. Each liquid crystal behaves in essence like a shutter or blind, and each represents a single pixel ("picture element"). As red, green, and blue light passes through the respective LCD panels, the liquid crystals open and close based on how much of each color is needed for that pixel at that moment in time. This activity modulates the light and produces the image that is projected onto the screen.

DLP ("Digital Light Processing") is a proprietary technology developed by Texas Instruments. It works quite differently than LCD. Instead of having glass panels through which light is passed, the DLP chip is a reflective surface made up of thousands (or millions) of tiny mirrors. Each mirror represents a single pixel.

In a DLP projector, light from the projector"s lamp is directed onto the surface of the DLP chip. The mirrors tilt back and forth, directing light either into the lens path to turn the pixel on, or away from the lens path to turn it off.

In the most expensive DLP projectors, there are three separate DLP chips, one each for the red, green, and blue channels. However, in most DLP projectors under $10,000 there is only one chip. To define color, a color wheel is used that contains (at minimum) a red, green, and blue filter. This wheel spins in the light path between the lamp and the DLP chip and alternates the color of the light hitting the chip from red to green to blue. The mirrors tilt away from or into the lens path based upon how much of each color is required for each pixel at any given moment in time. This activity modulates the light and produces the image that is projected onto the screen.

Sealed imaging chip. Most DLP projectors have sealed DLP chips that eliminate the possibility of a dust particle alighting on the imaging plane, which could create a dust spot on the projected image. LCD projectors do not have sealed panels, and the possibility of getting a dust spot exists. This is especially true when air filters are not cleaned periodically as per operator manual instructions.

Filter-free. DLP projectors that have sealed DLP chips can operate without air filters. Thus maintenance is reduced since there is no need to periodically clean or replace filters. Some vendors represent their DLP products as maintenance free, other than the occasional lamp change and dusting of the case and lens. Others don"t go quite that far, and recommend a periodic vacuuming of the air vents to limit the amount of dust getting into the unit. The vast majority of DLP projectors on the market do not have air filters, but some of the most expensive high performance 3-chip DLP models do, as do a few earlier generation DLP models that may still be in use.

Whether filter-free design is a true advantage to the user is a matter of competitive debate and controversy. In most DLP projectors, components other than the imaging chip itself are not sealed and can be adversely affected by a build-up of dust. In particular, dust on the color wheel may affect color and image quality. Dust particles can burn or melt when coming into contact with the lamp surface, thereby accelerating the degradation of lumen output over the life of the lamp. The degree to which a filter-free projector might be adversely affected depends on how much dust there is in the operating environment. Texas Instruments maintains that the amount of dust found in a normal room environment will not adversely affect the operation of a filter-free projector. Those who advocate the use of filters maintain that air filters will prevent an accelerated degradation of the lamp"s lumen output, even in normal room conditions.

Recognizing dust as a potential problem, Mitsubishi has taken extra steps to combat dust contamination in their latest filter-free DLP projectors, the XD3200 and WD3300. They have sealed the color wheel to prevent dust from reaching it. They have also made design improvements to the light pipe and airflow channels which reduce the amount of dust that can reach the lamp. These changes are intended to help maintain the lamp"s lumen output potential over its lifespan.

Those who advocate using air filters on projectors maintain that dust is never good inside a projector, and that the user is better off with a filtered design that prevents dust from entering the projector to begin with. All LCD projectors use air filters, as do some of the higher end 3-chip DLP models from vendors such as Runco and Digital Projection.

Those who support filter-free designs point out that many users of filtered projectors do not follow recommendations for cleaning or replacing air filters. If an air filter gets clogged over time, it can inhibit airflow, increase internal operating temperatures, and adversely affect the life of the LCD panels.

No convergence problems. All projectors using three imaging devices, whether they are LCD, DLP, or LCoS, must have all three devices aligned perfectly so that the red, green, and blue information for each pixel is in convergence. Over time, these three device systems can slip out of alignment. On occasion they can come out of the box, brand new, with slight convergence errors. Convergence errors can soften the projector"s image and create color artifacts where there shouldn"t be any.

The single-chip DLP design has a unique advantage over all three-chip or three-panel systems: since there is only one imaging chip, convergence problems don"t exist. There is simply nothing to go out of alignment.

Contrast advantages. Most business class DLP projectors (those intended for portable presentation or conference room use) have much higher Full On/Off contrast ratings than comparably priced LCD models. ANSI contrast figures are rarely published in the projector industry, but our measurements indicate DLP projectors usually have an edge over the LCD competition in ANSI contrast as well. However, with the introduction of inorganic LCD panels that are now used in most LCD 1080p home theater products, DLP"s traditional advantage in contrast within the home theater market niche has been neutralized to a large extent.

No image persistence. If one displays a static image for an extended period of time, an LCD projector with organic LCD panels may have a tendency to retain a subtle ghost of that image even after the subject matter is switched to another image. This does not occur on a DLP projector. Nor does it occur on LCD projectors that use inorganic panels.

Some of the advertising hyperbole has blown the seriousness of this issue out of proportion. Anti-LCD ads have claimed that LCD projectors are subject to "burn-in." Strictly speaking, this is not really true. Burn-in, in traditional usage, refers to permanent damage that can be suffered by CRT or plasma phosphor-based displays. Once a static image has been etched into a phosphor display through long term exposure, it cannot be removed. This is a different phenomenon than we see on LCDs. On organic LCD displays, when image persistence occurs, it is temporary and can normally be erased by displaying a white screen for a period of time.

Nevertheless, the point is that image persistence does not occur on either DLP projectors or inorganic LCD projectors. So on these products there is never any need to take steps to erase a persisting image.

No degradation of image quality over time. There is usually no degradation of image quality on DLP projectors when used over long periods of time, other than that which might result from excessive internal dust build-up. But in any event, the DLP chips themselves will not degrade. Conversely, LCD panels and polarizers can degrade with time, causing color shifts, unevenness of illumination, and reduction of contrast. The degree to which LCD degradation is a problem on current products is somewhat of a mystery since those who know the most about it (the LCD manufacturers) don"t discuss it publicly. This issue will be discussed further below.

Somewhat less pixelation/screendoor effect on low resolution products. One of the historical advantages of DLP over LCD has been a reduced level of pixelation in the image. Pixels tend to have sharper definition on an LCD projector, and this can produce a more visible pixel structure in the image. This is often called the screendoor effect, since the picture on low resolution projectors can look like it is being viewed through a screendoor.

However, the differences between LCD and DLP in this regard are not as great as they used to be for two reasons. First, LCD makers have achieved smaller interpixel gaps, making the screendoor effect much less visible. Second, the average native resolution of projectors being sold today has increased dramatically over what it was several years ago. With increases in resolution come smaller pixels and a less noticeable pixelation across the board. Nevertheless, on low resolution products like SVGA and even standard XGA, DLP projectors still have an advantage in manifesting somewhat less visible pixel structure than LCD projectors. (Note: There is a disadvantage to having less distinct pixel structure, which is reduced image sharpness. We will discuss this further below.)

DLP leads in miniaturization. The single-chip light engine affords the opportunity for extreme miniaturization that LCD cannot quite match. At the moment there are 15 DLP projectors on the market that weigh less than 3 lbs and put out more than 1000 lumens. By comparison, the lightest 3LCD projector on the market weighs 3.5 lbs and most are 4 lbs or more.

Color wheels can produce rainbow artifacts. The problem people point to most frequently as a weakness in DLP is its tendency to produce "rainbow artifacts." Rainbow artifacts (sometimes referred to as color separation artifacts) are momentary flashes of banded color that look like rainbows. They occur at random, and they only last for an instant. But for people who are sensitive to them, they can be quite distracting. If you are engrossed in a film or video, they can take you entirely out of the video experience.

Rainbow artifacts are a problem only on single-chip DLP products, and for the most part, only those using slower speed color wheels. They can also occur on LED-based models due to the sequential strobing of red, green, and blue LEDs. Typically the problem manifests itself when the viewer is watching movies or video. When viewing static images such as presentation charts or photographs, people generally do not experience the problem.

The rainbows occur because of the sequential color updating from the wheel or LED. As the color wheel spins or the LEDs change, the image on the screen is either red, green, or blue at any given instant in time. The technology relies upon your eyes not being able to detect the changes from one to the other. However, when your eye moves rapidly in response to some movement in the picture, you can get a red, green, and blue update on three different points on your retina, thus producing the impression of a rainbow. Not everyone perceives rainbows the same way. Many people have less sensitive eyes and cannot detect rainbow artifacts at all. Others see them quite readily. There is no way to know whether you are among those who can or cannot see them except by watching a DLP projector yourself.

Since LCD projectors and 3-chip DLP projectors always deliver a constant red, green, and blue image simultaneously, they do not create rainbow artifacts.

On DLP projectors with color wheels, rainbow artifacts are reduced by increasing the speed of the wheel. The first generation DLP projectors incorporated a color wheel that rotated sixty times per second, or 3600 RPM. With one red, green, and blue filter in the color wheel, updates on each color happened 60 times per second. This rotation speed in the first generation products was known as a "1x" rotation speed. In second-generation DLP products, the color wheel rotation speed was doubled to 2x, or 7200 RPM. The doubling of the color refresh rate reduced the time between color updates, and so reduced the visibility of rainbow artifacts for most people. But a 2x rotation speed was still not fast enough for products to be used in home theater and video applications.

Today, some DLP projectors being built for the home theater market use a color wheel containing two sets of red, green, and blue filters. This wheel still spins at 7200 RPM, but because red, green, and blue are refreshed twice in every rotation rather than once, the industry refers to this as a 4x rotation speed. And by increasing the physical rotatio

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey